The ongoing struggle for civil rights in Hawaii

The casual racism and the more ominous state-sponsored oppression that the TMT episode has brought to the surface are reminders that, like oppressed people throughout America and the world, Hawaiians are still fighting for civil liberties and equality under the law.

As protectors of Haleʻakalā appeared in a Maui court last week to be arraigned on charges related to their non-violent campaign to end desecration on the sacred Hawaiian mountain, social media buzzed with news of the unceremonious removal of the protectors’ tent on Mauna Kea, just after midnight, by 19 Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) officers. Underscoring the tension in this, now, six-month-old stand-off, are racial undertones that reverberate with disturbingly familiar patterns.

The ongoing onslaught of bigotry and hate speech targeting kanaka maoli (Hawaiian) protectors flared the same day of the arraignment in response to a Star-Advertiser story about the DLNR removal of the tent. Referring to the mostly Hawaiian protectors as a “stupid,” “uneducated,” “lazy,” “attention seeking” “bunch of malcontents,” online commentators to the story also denigrated kanaka maoli spiritual practices as a “hyped-up ʻreligion’” and called for destruction of the traditional hale pili, saying the state ought to “Take down the hale or set a match to it to burn it!”

As a journalist following the TMT controversy, I’ve archived dozens of bigoted, racist and incredibly ignorant comments on TMT-related articles. Here’s a sampling:

“Come on Americans let’s pack up and leave this little island and let the Hawaiians defend for their selves and we’ll see how far that gets them. We will make sure we take all of our work with us and all the assistance and I got a real good one for you we’re taking WIC to. F****** people are a joke.”

“I understand not liking the people who took over the islands of Hawaii but many who complain also like to forget the violence (including human sacrifice) that was common place and part of the culture before the missionaries came.”

“It is among native groups that I routinely witness some of the worst exploitative behavior. They take what they want without any regard for even the most simple management practices.”

“Well whether or not you are racist is entirely dependent upon your skin color. If you have dark skin then you get a free pass like me. If I had white skin I would immediately be branded a racist.”

“Many ancient and not so ancient cultures find human sacrifice to be sacred. In fact, Hawaiians did, at one time.”

“Imagine Hawaii with no federal assistance. Who would fill your EBT cards?”

“Many of us who voted for David Ige are disappointed with his lack of leadership. …We only can hope he will take a firmer hand now and not let the state of Hawaii revert to the Stone Age.”

“THIS GROUP IS THE SPARK TO A FULL BLOWN TERRORIST ORG/GROUP.”

“Sad to say the Hawhiners are illiterate, can’t read and comprehend this. Only stuck with their blinders on, very limited point of view.”

Going beyond obvious comparisons between the bigotry leveled at Hawaiians and the bigotry against other minorities, the oppression of kanaka maoli culture witnessed on Mauna Kea and Haleʻakalā has parallels to the oppression endured by other groups, including African Americans during the time of the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Anti-Hawaiian racism has been evident from the earliest days of the Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT) stand off. Much of the racist commentary documented above comes from people who have no direct ties to the astronomy community; people who would find some other way to be bigots even if the TMT project was canceled. But, in April of 2015, a now notorious email from University of California, Santa Cruz, astronomer Sandra Faber was leaked to the public showing that even the scientific-community can be a haven for racism. Outraged fellow astronomers leaked her email after she referred to TMT opponents as “hordes of Native Hawaiians…lying about the impact of the project on the mountain and who are threatening the safety of TMT personnel.”

In recent weeks, similarities between the modern Hawaiian civil rights struggle and the ongoing struggles of groups like African Americans have become even more apparent as the thumb of state-sponsored oppression continues to strip away the freedoms ostensibly guaranteed to kānaka under the U.S. Bill of Rights, the 14th Amendment and the Traditional Customary Rights clauses of the Hawaiʻi State Constitution.

Freedoms Trampled Upon

Perhaps the most painful attack on kanaka maoli civil liberties comes in the form of religious desecration. Both the TMT and the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST, formerly the Advanced Technology Solar Telescope, ATST) on Maui are, by their very nature, examples of desecration of sacred space and exploitation of indigenous place. However, religious oppression comes in more forms than just the metaphysical issue of implicitly lessening that which is important to a different group of people. Day-to-day, actual instances of religious oppression can be equally disturbing and harmful.

A glaring example came earlier this month when an Office of Mauna Kea Management (OMKM) worker destroyed an ahu (shrine) that had served as a spiritual focal point for the protectors throughout the summer. The act of violence was reported by protectors in a Naʻau News Now video update on September 13. This type of violence falls under the same category as the kind inflicted by white supremacists who bombed and burned Black churches in 1963, albeit on a less horrific scale. And, while the casual bull-dozing of the altar may or may not have been intended as a form of oppression by the OMKM worker himself, he still participates in state-sponsored oppression by doing so, striking at the spiritual core of the protectors just the same as if he had burned the ahu to the ground.

“The ahu o ka uakoko once stood here and it represented the resurgence and the rebirth and the strengthening of our culture and our religion and our people and our spirituality and our sovereignty,” says Pueo McGuire in the video update, standing beside a visibly upset Joseph “Jojo” Henderson at the site where the ahu once stood.

“I used to come up here usually every second Sunday to clean the ahu,” Henderson says, his voice cracking with emotion. “Now we can’t even pray. Everybody else in this world can pray, but we can’t pray, as kānaka. That’s not right, brah.”

The ahu, which stood at the 11,000-foot elevation level of the mountain, was built by more than 100 protectors who passed pōhaku (stones) hand-to-hand to create the 4-foot tall altar.

Erected on June 24, 2015, the same day Hawaii County police arrested more than 20 Mauna Kea protectors, the ahu had spiritual significance to all those who stood in the lines along the Mauna Kea Access Road as human barricades to block construction crews from reaching the TMT construction site.

In an interview, Henderson said thousands made pilgrimages to the ahu over the summer, and that he went up about 100 times himself “just to clean up the hoʻokupu—the gifts—that people bring. I take care of all the old stuff to make sure it looks nice and clean. The ti leaves would get old, and all the gifts would get old I would come and grab them, bury them and take care of them the way I’m supposed to; the way I was taught.”

Henderson and other protectors created Naʻau News Now as a citizen journalism vehicle, providing daily Facebook video updates from Mauna Kea to the community. In the Hawaiian language, “naʻau” means gut—the spiritual spiritual center of being for kanaka maoli.

With a DLNR media ban in effect during all Mauna Kea arrests made during the 120-day period since the passage of emergency rules drafted by the agency and approved by Governor Ige, Naʻau News Now videos provide the only primary source alternative to the official, state-sanctioned arrest videos created by DLNR agents.

As stated in an Aug. 1, 2015 Star-Advertiser editorial, “The state Department of Land and Natural Resources’ media blackout on its enforcement of an emergency rule limiting late-night access to Mauna Kea is an affront to the public interest, and to the First Amendment.”

Since imposing the media blackout, DLNR officers have made two midnight raids on the protectors. In the most recent raid, officers on Mauna Kea took seven women into custody at 1 a.m. while in the act of prayer. Video of the arrests shows the non-resisting women being manhandled, and exclaiming in pain as their wrists are forced into in zip ties.

In testimony before the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) board of trustees the following day, Mauna Kea protector Hāwane Rios tearfully recounted the indignity and unnecessarily rough treatment the women were subjected to.

“We were in pule. We were in prayer,” recalled Rios. “They came in and broke our arms apart while we were right in pule with no explanation. They put us in zip ties.”

Members of the OHA board of trustees, several of whom had visited the protectors’ Kū Kiaʻi Mauna camp earlier the same day, were moved to action.

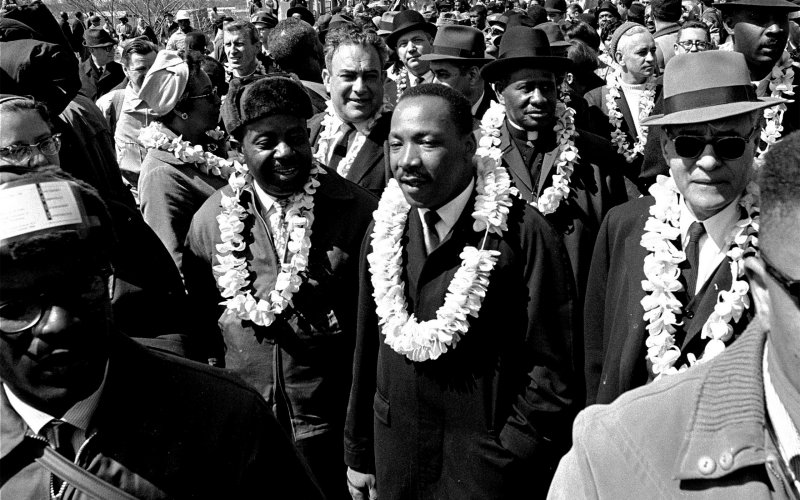

In this file photo of the 54-mile third march from Selma to Montgomery on March 21, 1965, Martin Luther King, John Lewis and other demonstrators wear lei sent from Native Hawaiians as a sign of solidarity.

Traditional and Customary Rights

OHA has condemned the arrests in an official video, calling on DLNR to cease further enforcement action, pointing out violations of the protectors’ U.S. Civil Rights as well as their Traditional and Customary Rights under the Hawaiʻi State Constitution.

The video poses the question, “When is it illegal to practice your culture?” and features protectors’ accounts of being treated roughly by police, and of being singled out for violating the emergency rules, which ban being on the Mauna Kea Access Road or its environs after 10 p.m., unless in a moving vehicle.

“We can no longer tolerate being victims of the state and deprived of our right to exercise our traditional, customary practices,” says OHA Ka Pouhana (Chief Executive Officer) Kamanaʻopono Crabbe, in the OHA video.

Meanwhile, the protectors say they have witnessed busloads of tourists stargazing on the mountain night after night without being disturbed, much less arrested.

In the OHA video, Lanakila Mangauil points out the unequal treatment. “This morning after the arrests—shortly after—and a little down the road, there was a tour van … right down the road. The officers didn’t arrest them,” says Mangauil. “They come up here ready to take on one specific group of people.”

“This government is not set up for us,” laments Rios in her OHA testimony. “It is not set up to protect us.”

A pillar of American Civil Rights since passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868, the Equal Protection Clause, has been the prohibiting of states from denying any person “equal protection of the laws.”

OHA attorney Robert G. Klein says the Emergency Rules go too far. “It essentially regulates the practice out of existence,” says Klein in the video. “If we are to understand the facts of arrests in Mauna Kea, we had a group of Hawaiian people, in a circle, praying—exercising their religious freedom—when they were arrested. The government interfered with that practice, which was wasn’t harmful to anybody. It was a valid, heartfelt, traditional practice and worship, and it shouldn’t have been interfered with.”

Expanding on the Traditional and Customary Rights of kanaka maoli enshrined in Article XII; Section 7 of the Hawaiʻi State Constitution, Klein is emphatic that, “Those rights that are embodied in there are constitutional values. They are just as important as any other constitutional value. And so they deserve the same amount of protection.”

However unnecessarily rough the handling the women on Mauna Kea was, those events were tame compared to the August 20 confrontation on Maui between demonstrators and Maui County police, who used militarized tactics to disperse the crowd of Haleʻakalā protectors; eight were arrested.

When is it illegal to practice your culture? from Office of Hawaiian Affairs on Vimeo.

Police Brutality

It began peacefully: a somber gathering of individuals and families at Central Maui Baseyard the night of August 20. But, by early morning, the scene devolved into chaos. Video, live-streamed by citizen journalists, showed a calm mood at the baseyard, as a crowd of more than 100 gathered to engage in cultural practices including pule, oli (chants) and hoʻokupu of several hundred flower and ti leaf lei.

For more than an hour, a procession of men, women and children came forward to place offerings to the sacred mountain upon a specially made bamboo altar. Things changed quickly, however, after police blared a five-minute warning for the crowd to disperse, and then emerged in a sea of blue from behind a chain link fence. Forming themselves into a human wall, the officers began to push forward. The situation grew increasingly intense as the officers pressed up against the flower laden altar. On the alter’s opposite side, a line of protectors held it steady. Video shows protectors, including Walter Ritte, consulting with police officers as they slowly continue to push the protectors and alter away from the park gate, eventually splitting them into two groups and forcing them to opposite sides of the road to clear a path for trucks carrying materials for the telescope. Ritte and others are able to peacefully remove the alter as they are forced aside, preventing it from being destroyed.

By the time the 18 wheelers started driving through the gate, some protectors had already left the baseyard and headed up to Haleʻakalā to set up a blockade on the road ahead of the convoy of police vehicles and trucks. Molokaʻi resident Shane Louro, 39, was among a group of five protectors who waited in the dark roadway, seated on the ground with their arms and legs intertwined, as the convoy snaked up the mountain.

After arriving, Louro said, the officers formed a wall with their riot shields that, when it opened, disgorged 30 to 40 officers in full riot gear who charged into the circle of praying and chanting protectors.

One of the burliest officers locked eyes on Louro. “When those cops came through, they came like a feeding frenzy of sharks,” recalled Louro. “That one cop he came straight for me. He bent my arm almost straight up and down with my spine.”

Louro, a widower and father of two boys, had his right shoulder partially dislocated and his rotator cuff torn by the officer, whom Louro guessed outweighed him by a factor of two to one. Currently with his shoulder in a sling, Louro hopes his injuries don’t prevent him from resuming coaching two youth basketball teams this season.

Henderson, 26, the other protector injured in the raid, had just finished performing a haka (traditional Maori dance) and was sitting on the ground with two others, behind the first circle of protectors, when the officers rushed forward in formation.

“There was one guy choking and one guy pushing on my nose,” said Henderson. “They couldn’t get my head back so they put their fingers up my nose and ripped my head back.”

Henderson, a veteran protector of the Mauna Kea vigil, said the experience was dehumanizing.

“What was going through my mind was how wrong it is that I feel less of a person, you know? They’re treating us as less than human,” said Henderson. “They’re criminalizing us and doing selective enforcement just on us, and putting ridiculous bail amounts on our heads ‘cause they know that we don’t have that much money.”

The Big Picture

Putting these arrests into the context of the larger American picture of mounting police brutality and attacks on African Americans and their churches—including the horrifying June 17 massacre at the Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina—the culture war on kanaka maoli civil rights may appear mild. But the similarities are, nonetheless, unsettling. Certainly the current disregard of the civil rights of Hawaiians does not speak or bode well for the State of Hawaiʻi.

Whether it be unfettered observatory development on sacred mountains, bulldozing an ahu, or brutal arrests conducted during religious ceremony, attacks on kanaka maoli cultural values are on the rise. Thankfully, the attacks on African American civil rights have raised cries for justice from the general public but, as of now, such condemnation for injustices toward kānaka are lacking in Hawaiʻi nei.

Lack of education and understanding of kanaka maoli culture, history and struggle certainly play a part in this general silence toward Hawaiʻi’s civil rights violations. Though mandated by the Hawaiʻi State Constitution since 1978, Hawaiian history and cultural education have yet to be sincerely implemented into the curriculum of Hawaiʻi’s public schools.

Further reasons for the lack of equal treatment and respect for traditional Hawaiian culture may stem from the fact that, rather than erecting solid-walled structures like churches, synagogues or mosques, Hawaiian cultural practitioners, as their ancestors before them, revere natural settings like the summits of Mauna Kea and Haleʻakalā as sacred instead.

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Professor of Sociology Kalei Kanuha calls these differences in perception a “value gap.” While Kanuha says the general public understands things like the taking down of a cross, or the writing of graffiti on a synagogue, as acts of bigotry. But destruction of traditional kanaka maoli sacred places and objects isn’t necessarily viewed that way.

“The difference, I think, is that a church or synagogue or mosque is a site that is very well known to the general public as a symbol and place that represents significant world religions. I don’t think people think about [Mauna Kea] that way … We [Hawaiians] don’t have the same kind of public acknowledgment, public affirmation, or public awareness about what might be considered sacred to us as an object or a place or a site.”

The idea that Kanaka Maoli ahu and heiau (temples) are viewed as less significant because they’re built of stone instead of bricks and mortar resonated with Kanuha. “I definitely agree with that,” said Kanuha. “I think you’re right: using stones—living pōhaku—versus bricks and mortar is the perfect metaphor for what is valued. When you can see rocks everywhere and you don’t see bricks and mortar everywhere … the commonality of it does not give it the same kind of apparent value, no matter how you put it together.”

Despite the current culture of oppression faced by kānaka, the parallels with 1960s-era oppression of Blacks and other minorities, and the disturbing trends of police brutality and racism rising across America today, there is also a history of spiritual connections between Hawaiians and African Americans that endures as a legacy to nurture the strength of the protectors’ Kapu Aloha, and to guide the Aloha ʻĀina Movement forward. It was in 1965, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, that, in a gesture of spiritual solidarity, physical representations of aloha sent from kānaka were able to bolster the ultimate moral victory of the historic day that came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

As Marin Luther King, Jr. led thousands of non-violent protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the iconic third march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, he and dozens of his followers were adorned with flower lei sent from Hawaiʻi as a talisman of aloha and protection. It may be a casual association, but Hawaiians like me know a hoʻailona (a sign of other forces at work) when they see it.