Battleship Guam

U.S. militarism has turned islands into targets and peoples into weapons: Only a movement for peace will save the Pacific.

Cover photo: ANDERSEN AIR FORCE BASE, Guam—F-15E Strike Eagles and a B-2 Spirit bomber fly in formation over the base. The Strike Eagles are with the 391st Expeditionary Fighter Squadron from Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho. The bomber is from the 325th Expeditionary Bomb Squadron from Whiteman AFB, Mo. (U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Cecilio Ricardo) | Wiki Commons

“Guam, objectively, has the highest ratio of US military spending and military hardware and land takings from indigenous populations of any place on earth.” —Catherine Lutz, “US Military Bases on Guam in Global Perspective”

—

Last month, when the Guam Homeland Security and Office of Civil Defense released a two-page fact sheet on how to prepare for and survive a nuclear attack, I worried about my 95-year-old grandma. She lives in a small village near Hagåtña, the capital of Guam. On most days, you can find her at a community center playing bingo.

Decades ago, my grandma would pick up my sister and me from elementary school. We knew when she won at bingo because she would smile and take us to McDonalds for a snack. After, we stayed at her house and played in the backyard amongst mango, guava, banana and coconut trees. Our games were only interrupted by the sonic blast of fighter jets flying overhead.

To grow up on Guam is to grow up in a deeply militarized and colonized place. American bases occupy nearly 30 percent of the territory. Two of the main highways are “Marine Corps Drive” and “Army Drive.” The road from my grandma’s house to my former elementary school is “Purple Heart Highway.” Barbed wire fences with “No Trespassing Signs” snake across our island.

—

Guam became an unincorporated territory of the United States after the Spanish-American War of 1898. In 1941, the Japanese military bombed and invaded Guam, just a few hours after the Pearl Harbor attack. Unlike Hawaiʻi, the imperial army successfully defeated the American forces and occupied Guam.

My grandma, who was 19 years old at the time, survived the 32-month Japanese occupation. Traumatic stories of war, removal, forced labor, rape, beheading, kidnapping, disappearance, murder, mass graves and death marches continue to haunt our people even generations later. A thousand Chamorros from Guam’s “greatest generation” were taken from us.

After the U.S. won the devastating “Battle of Guam” in 1944, the Department of Defense began to fully militarize the reclaimed territory. Chamorro families, and even entire villages, were evicted from our ancestral lands for the construction of bases. Andersen Air Force Base would become the main airfield for Operation Arc Light, the infamous bombing campaign during the war in Vietnam. Today, Andersen houses the B-1B Lancer, the B-2 Spirit, and the B-52 Stratofortress—the first time in history these three bombers have been in the Pacific at the same time. Naval Base Guam, located on Apra Harbor, would become a crucial location for the Pacific fleet and squadron of submarines. Beyond bases, Guam is also one of the largest munitions depots in the world, storing millions of bombs, missiles, bullets and other weapons that supply the global American war machine. Furthermore, Guam is a major landing station for undersea cables that carry almost all trans-Pacific internet traffic—important infrastructure for any cyberwar.

Guam’s “strategic location,” “strategic geography” and “strategic political status,” make it one of the most important military bases in the world. This is why Guam is often referred to as “USS Guam,” “Unsinkable Aircraft Carrier,” “Superfortress Island” and “The Tip of America’s Spear in Asia.”

—

Guam’s environment has been severely impacted by militarization. Construction, training, testing and weapons storage have destroyed and contaminated our lands and waters.

Coral reefs have been dredged, fishing grounds have been poisoned and marine life have been killed. Guam was once a place of abundance and biodiversity; today, nearly a hundred contaminated dumpsites and Superfund sites plague our island. After decades of exposure to toxins, my people (the indigenous Chamorros) suffer disproportionately high rates of various cancers and neuro-degenerative diseases. Moreover, toxic masculinity has resulted in countless sexual assaults perpetrated by American soldiers beyond (and within) the fence line.

While our island is used as a military base, our bodies are used for soldiering. Since Chamorros were granted U.S. citizenship in 1950, we have been drafted and/or enlisted into the armed forces at the highest rates, per capita, of any other state or territory. My father served in the Army and fought in Vietnam, and many of my relatives have, and continue to, serve in all branches of the military. This is why Guam is called a “Military Recruiter’s Paradise.” Despite this patriotism, Guam ranks last for Veterans Affairs funding per capita, giving us another nickname: “The Island of Forgotten Warriors.”

Another military impact is the out-migration of the Chamorro population and the in-migration of settlers to Guam. Before 1950, nearly all Chamorros lived in our home islands and comprised 90 percent of Guam’s population. Today, Chamorros only comprise 40 percent of the population, and many settlers to Guam arrived as part of the labor force for military construction. Today, off-island Chamorros now outnumber our on-island kin. According to the U.S. census, 140,000 Chamorros live in the states, whereas only 65,000 Chamorros live on Guam. The main reason why Chamorros have migrated is because of military service. Our largest diasporic population lives in San Diego, California—another deeply militarized place. The Chamorro people are now classified as the most “geographically dispersed” of all the Pacific Islander populations within the United States.

—

My own family migrated from Guam to California in 1995, when I was 15 years old. I attended high school, college and graduate school in the Golden State. In 2006, news about a plan for a massive military buildup on Guam began to circulate.

This massive military buildup included the relocation of thousands of marines and their dependents from Okinawa to Guam, the berthing of nuclear powered aircraft carriers in Apra Harbor, the establishment of an Army Air and Missile Defense Task Force, and the creation of a live firing range complex. The Environmental Impact Statement detailed how this hyper-militarization would further desecrate our land and water, destroy the forest and coral reefs, and increase the amount of hazardous waste and incidences of violence and sexual assault.

The buildup extends to several northern islands in the Marianas archipelago, of which Guam is the southernmost island. The military plans to turn two-thirds of the island of Tinian and the entire island of Pagan for live fire bombing and training. Increased bombing will be approved for the island of Farallon de Medinilla, which has been used as a firing range for decades. The military plan has also extended to our waters. The Mariana Islands Range Complex (MIRC) established half a million square nautical miles for a live-fire training range in the waters around the archipelago. More recently, the proposed Mariana Islands Training and Testing Area (MITT) will double the area of the MIRC to nearly a million square nautical miles (the size of Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, Arizona, Montana and New Mexico combined). The MITT allows for 12,000 detonations per year, 80,000 takings of different marine mammal species per year, and the damage or kill of over 6 square miles of endangered coral reefs.

Taken together, the U.S. military will control more than a quarter of the total landmass of the Marianas archipelago, along with the entirety of our territorial waters and airspace—creating America’s largest training and bombing range in the world.

As if this wasn’t enough, the biennial war games, Exercise Valiant Shield, occurred for the first time in and around the waters of the Marianas in 2006. This show of force—involving 22,000 military personnel, 280 aircraft and 30 ships—was the largest in the Pacific since the war in Vietnam.

The planned military buildup and the ongoing military exercises sparked a new wave of demilitarization activism across the Marianas archipelago and the Chamorro diaspora.

I joined a California-based Chamorro activist group called Famoksaiyan in 2006. We organized many events across the state (44,000 Chamorros reside in California) to raise awareness about militarism and colonialism in our homelands. In 2008, a delegation of us traveled to the United Nations in New York City for the meeting of the Special Committee on Decolonization, which advocates for the remaining non-self governing territories (or colonies) in the world. When we began our testimonies, the U.S. representative walked out of the room. To be Chamorro is to be unheard and invisible. To be from the Marianas is to be from a place that most of the world does not know or care about.

—

The only time the world sees us is when the crosshairs of a missile is upon us.

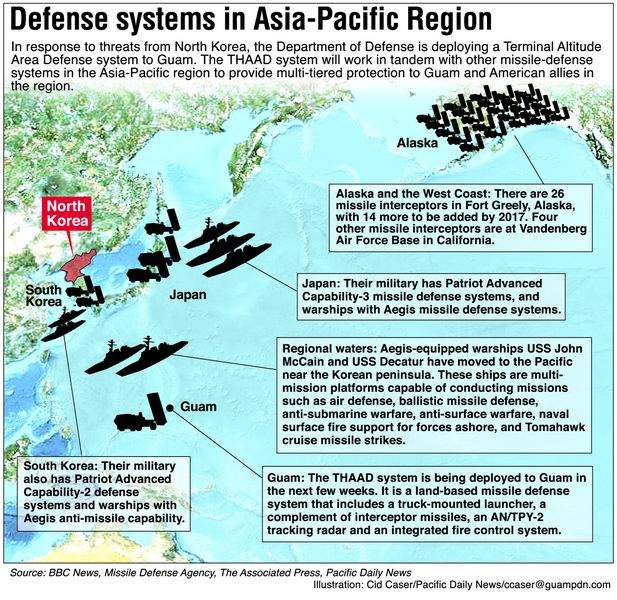

Guam made international headlines in 2013 when North Korea threatened the island in response to the U.S. military buildup and exercises in the region. I wrote an article that year titled, “A Kite of Words for the Korean People,” in which I highlighted how militarism has woven together the histories of the Marianas and Korea. I argued that war rhetoric functioned to make us feel afraid because if we feel afraid, then we will embrace the U.S. military as our protector and consent to endless militarization. I argued that war rhetoric also justified the approval of massive U.S. military budgets, as well as expenditures on new weapons, such as the deployment of the $800 million Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system to Guam.

The tension between North Korea and the United States reached a feverish, viral pitch last month because of Trump’s strategic spectacle (as opposed to Obama’s strategic patience in 2013). Hundreds of articles, op-eds, radio interviews, and television shows broadcast Guam to the world. The global media struggled to “Guamsplain” basic facts and to explain Guam’s complex (and often curious) culture, history and politics to a world that is more comfortable ignoring colonial territories.

For a few days, Guam walked the global catwalk as Miss Universe in the Trump pageant. Guam’s governor was juxtaposed with the co-chairs of the Independence for Guam Task Force. Guam’s (non-voting) congressional representative was juxtaposed with Guam’s professors. Guam’s concerned citizens were juxtaposed with Guam’s unconcerned citizens. Guam’s military personnel were juxtaposed with Guam’s tourists. Guam’s “tiny” size was juxtaposed with its huge importance to American power. Guam’s patriotism was juxtaposed with Guam’s independence movement. Guam’s citizenship was juxtaposed with Guam’s lack of voting rights for president. Guam’s brown tree snakes were juxtaposed with the absence of Guam’s native birds. And Guam’s fear of nuclear war was juxtaposed with Guam’s confidence in the American military.

—

As I have written before, the military buildup and exercises between the U.S. and South Korea, as well as nuclear weapons development in North Korea, has created a disconcerting and volatile situation in the Asia-Pacific region. However, the rhetoric and media coverage has often cast American militarism as the protector and savior, which masks the ongoing damage that it has caused to our lands, waters and bodies, as well as the ongoing provocative and belligerent atmosphere it has stirred.

One reason this rhetoric is important to American military interests is because it helps overshadow demilitarization movements and critiques, which have been present and growing in Guam, the Marianas, Okinawa, the Philippines, Hawaiʻi and Jeju Island in South Korea. Last week, a teach-in was held at the University of Guam to inform the public about the MITT and to encourage people to submit comments during the public comment period, which closes on September 15, 2017. Another group, “Prutehi Litekyan: Save Ritidian,” has been holding protests to stop the building of the live firing range complex in an area of Guam that is a wildlife refuge, archaeological site, ancestral land for families that were evicted and limestone forest. Other groups, such as Alternative Zero Coalition, the Guardians of Gani, Tinian Women’s Association, Pagan Watch and Earthjustice are fighting (through lawsuits and public awareness campaigns) to protect Pagan, Tinian and Farallon de Medinilla from being used as bombing ranges.

The escalated rhetoric is also being used to justify military budgets, expenditures and defense industry profits. The first squadron of combat ready F-35 Lightning II fighter jets have recently been deployed to the Pacific. The $1.5 trillion program for these high tech warplanes is the most expensive in history, and is being completed by Lockheed Martin, the largest weapons manufacturer in the world (they also produce the THAAD at $800 million per system). Other defense contractors, such as Raytheon, Orbital ATK and Aeroject Rocketdyne, Boeing, BAE Systems and many others will profit from the military buildup, and their stocks will skyrocket if the U.S. decides to attack, invade and occupy North Korea.

Trump has made it clear he intends to increase military spending and arms exports. The U.S. spends more on military and weapons than any other country in the world, and U.S. defense corporations dominate sales in the global defense industry. The fact that Trump has filled his cabinet with military generals is another sign of this administration’s pivot towards war. Relatedly, the defense industry in South Korea is a growing part of its economy and has close ties to the U.S. industry. Indeed, South Korea has become a major weapons dealer in Asia and may soon outpace China.

Since the global spotlight moved away from Guam, two military contracts have been awarded: a $78 million contract to Black Construction Corp for the construction of the firing range and a $165 million contract to Granite-Obayashi for construction of the new Marine Corps base. Military profits flow in the wake of war rhetoric.

—

Currently, I live and work in Hawaiʻi, which has a similar history to Guam in terms of U.S. colonialism and militarism. Thousands of Chamorros live in Hawaiʻi as well, most of whom are connected to the military.

Hawaiʻi is home to Pacific Command, which is responsible for military operations in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region, comprising half of the Earth’s surface, half the world’s population, and 36 nations. The U.S. military occupies about 20 percent of the land area in the Hawaiian archipelago, and over 400 toxic military sites exist here. The world’s largest international maritime military exercise, known as the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC), takes place biennially in Hawaiʻi and its waters. RIMPAC includes over 20 participating countries, and these war games also act as marketing showcase for weapons sales and manufacturers.

Last month, Hawaiʻi became the first state to prepare for a nuclear attack in response to the threats from North Korea. While it will take 14 minutes for a ballistic missile to strike Guam from North Korea, it will take about 20 minutes to reach Hawaiʻi. The Hawaiʻi Emergency Management Agency is preparing a public information campaign with a revised set of nuclear response guidelines for residents. Additionally, the agency is reinstating statewide warning sirens, which have not been used here since the Cold War, as well as a warning system for cellphones. Just a few days ago, the U.S. missile defense agency and the Navy conducted missile defense tests off the coast of Kauaʻi.

When we question the rhetoric of heroic American militarism, we see how the militarization of our homelands does not make us safe and secure. Instead, it turns our islands and peoples into weapons and targets. It turns our islands into bases for destruction and corporate profit. It turns our islands into bombing ranges and toxic sites. It turns our islands into collateral damage and sacrifice zones. It turns our ocean into a battlefield.

—

My mom, who still lives in California, called me after she heard about the nuclear attack preparations in Hawaiʻi. She had been worried about our relatives on Guam, and she was now worried about my family too. My three-year-old daughter had just started her first week of preschool, and my wife, who is Native Hawaiian, is seven months pregnant.

I think about all that my grandma has witnessed during her lifetime. The violence and death of World War II. Decades of land eviction, militarization and contamination. So many of our relatives dying from cancer. So many of our relatives being deployed to fight and die in American wars. So many of our relatives migrating off-island. All of our native birds disappearing. And I think about all the inspiring, brave and empowering demilitarization activism that has emerged during her lifetime. This gives me hope to imagine a different future.

During my children’s lifetime, I want them to witness the demilitarization of their ancestral home islands. I want them to witness the rehabilitation of our lands and wildlife and the healing of our bodies and souls. I want them to witness the decolonization of the Pacific and the establishment of indigenous sovereignty and governance. I want them to witness nuclear disarmament. I want them to witness just and compassionate compensation to all those who have been impacted by uranium mining, nuclear testing and nuclear war. I want them to witness nations dedicate their budgets to education, health care, sustainability and the arts, as opposed to the military. I want them to witness a new world in which we act with the beliefs that our islands are sacred, all life is interconnected and the ocean is source. I want them witness our islands become sites of genuine security and diplomacy. I want them to witness the proliferation of peace.

Craig Santos Perez is a native Chamoru from the Pacific Island of Guåhan/Guam. He is the co-founder of Ala Press, co-star of the poetry album Undercurrent (Hawaiʻi Dub Machine, 2011), and author of two collections of poetry: from unincorporated territory [hacha] (Tinfish Press, 2008) and from unincorporated territory [saina] (Omnidawn Publishing, 2010), a finalist for the LA Times 2010 Book Prize for Poetry and the winner of the 2011 PEN Center USA Literary Award for Poetry. In 2017, Perez became the first native Pacific Islander to win the Lannan Foundation Literary Fellowship for Poetry. He is an Assistant Professor in the English Department at the University of Hawaiʻi, Mānoa, where he teaches Pacific literature and creative writing.