What really happened at the ʻAha, part III

Impediments to carrying out the people’s business continue throughout the final days of the convention.

Above: Protesters gather outside the gates of the Royal Hawaiian Golf Course on February 22. ʻAha officials did not allow outside observers or media to witness the convention’s proceedings, something that did not sit well with all the participants.

Editor’s note: As one of the 154 kānaka maoli who agreed to participate in the state-sponsored, Naʻi Aupuni-initiated Native Hawaiian ʻAha, Kaʻiulani Milham had a front row seat at the month-long proceedings. What follows is the third installment of a multi-part, first-hand account that highlights various and consistent affronts to democratic processes that ruled during the ʻAha proceedings. Read part I, part II, part IV and part V

Two days before the end of the ʻAha, pressure from the federal recognition side was mounting to finish the constitution. The various committees had submitted their input to the drafting committee and now awaited the result. Those in the preamble committee were edgy. Twice now, the input the preamble committee had sent to drafting had come back altered to remove provisions for full sovereignty and independence they had written in. By this point in the process, disillusionment had become a familiar feeling.

After years spent reporting on municipal governments in California, I was accustomed to “Sunshine Laws” protecting the public’s right, barring certain exemptions, to know exactly what goes on in government meetings. According to the 1976 federal Sunshine Act:

...every portion of every meeting of an agency shall be open to public observation.

...the people are the only legitimate foundation of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter ... is derived. Government is and should be the servant of the people, and it should be fully accountable to them for the actions which it supposedly takes on their behalf.

But, throughout the entire process, ʻAha officials disallowed outside observers, including media. While protesters petitioning for admittance were ignored or arrested outside the locked gates of the Royal Hawaiian Golf Club, the ʻAha communications committee was disseminating bulletins to media outlets and the general public that were meant to give an impression that all was going smoothly.

The ʻAha may not have been a governing body of elected officials, but we were still there, ostensibly, to draft the governing documents necessary to create a government. Sunshine Laws are meant to apply to entities that create binding laws within such a government so that the public can ensure those laws are just. What does it say about a government that won’t allow the public to ensure its very formation is just, let alone the binding laws it would proceed to enact once formed?

Above: Members of the preamble committee observe changed language on a projector with mixed reactions.

Censored From the Start

Three weeks earlier, the purpose statement had established the work of the ʻAha: “draft a constitution that establishes a Native Hawaiian government.” Thereafter, the ʻAha meeting hall had become a hive of activity. Bringing the participants together and inviting them to express their personal concerns gave them each an emotional stake in the final outcome of the process.

Given 3x5 note cards upon which they could write their concerns and issues, participants expressed a range of concerns that were deposited in baskets labeled “Judiciary,” “Individual Rights,” “Collective Rights,” “Executive” and “Legislative.” Once the cards were collected in their appropriate baskets, they underwent additional screenings. Assigned to designated tables based on these categories, participants were given newsprint sheets upon which to list what participants had written on the cards, after eliminating redundancies and shuttling cards that didn’t seem to fit the given category to more appropriate tables.

At the “Individual Rights” table, the illusion of a democratic process quickly dissolved. Dreanna Kalili, of Makalehua (the self-described group of “young Hawaiians”) assumed control of sorting the cards, and Annelle Amara, president of the old guard Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs and a federal recognition stalwart, took control of the Sharpie as the self-appointed arbiter of the table’s list.

At one point, a participant who works in the foster care system approached our table to share her concerns about the need to ensure Kanaka Maoli children are protected, including from adoptions that may subject them to abuse or that might separate them from the lāhui.

After arguing against the wisdom of including such a provision in the constitution, Amaral agreed to its inclusion, while simultaneously reducing the woman’s detailed outpouring of concern into a two-word bullet point: “protect children.”

Was this an isolated case or was this not-so-subtle attempt to corral—and sometimes censor—the discussion going on at the other tables too? The answer would reveal itself plainly in the ensuing plenary session.

Meanwhile, the leadership team announced the formation of committees based on the input from the note cards and representing various sections of the proposed constitution that had categorized the baskets and note cards, as well as a stand-alone preamble committee. These committees were to discuss and refine the applicable input into more concrete language that would then be forwarded to the drafting committee. Participation in committees was to be determined by “law of feet”—anyone who wanted to participate in a particular committee could do so. But time and again, throughout the following weeks, participants were disappointed to find specific provisions they had put forward, both on the 3x5 cards and in committees, had been edited out by the drafting committee.

Above: Lunakanawai Hauanio shows some of the many documents he brought to the ‘Aha to protesters at the Royal Hawaiian Golf Club gates. Hauanio helped start the international committee with a goal of preserving the option of full independence.

Pursuing Independence

By that third week, independence advocates had seen enough of the ʻAha agenda to have no further illusions about their place at the table. The clear objective was to create a document that would facilitate federal recognition. Advocates who wanted to promote the possibility of a future independent Hawaiʻi were on their own.

Meanwhile, in local broadcast media, the federal recognition leaders were pushing their message at every opportunity.

“Certainly, independence is not a viable option. It’s just not viable. The United States itself will not allow one of its states to secede from the union,” Amaral told Hawaii News Now.

Furthering the independence agenda in this sometimes hostile environment would require organization. But the elected ʻAha leadership team, taking an opposite approach from the hired facilitators who had temporarily organized the ʻAha into “independence” and “federal recognition” caucuses, had now separated participants by committee without creating a committee for independence advocates to focus on their concerns. Instead, the committees they had organized were specific to the various sections of the federal recognition-friendly constitution they were intent on drafting.

Taking matters into their own hands, Hawaiʻi island participants Lunakanawai Hauanio and Keoni Choy organized a new committee on February 17: the international committee began to discuss drafting documents for restoring an independent Hawaiian government.

This committee, which included 15–30 members on any given day, discussed several options for models on which our governing documents could be based. These options included the 1999 ʻAha Hawaiʻi ʻŌʻiwi (AHO) constitution offered by Honolulu attorney and long-time sovereignty activist Keoni Agard. Agard was one of a handful of participants who were elected to the AHO Constitutional Convention and whose work was interrupted when, after the determination of that elected body was to seek independence from the United States, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) pulled the convention’s funding.

In addition to the AHO constitution, the committee looked at a Unicameral Independent Constitution drafted by former Hawaiʻi State Representative Jimmy Wong.

Waiʻanae attorney Poka Laenui, a long-time sovereignty activist, offered the body several documents for consideration, including a “Hawaiʻi National Transitional Authority” plan that could potentially bridge federal recognition and independence factions. Laenui also proposed an international relations unit that would be tasked with building support within the international community for a Hawaiian nation.

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Richardson Law Professor Williamson Chang, offered his own “Maunawili I” and “Maunawili II” documents to the committee: short and long declarations detailing the legal justification for Hawaiian independence predicated on the argument that the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists, however “atrophied” in form, while it remains in a state of prolonged occupation by the United States of America.

ʻAha chair Brendon Lee made it clear that participation in the drafting committee was likewise open to all who were interested. The initial meeting of the drafting committee took place in a small side room, which was already packed when I arrived. Apparently the response was more than leadership had bargained for. Some culling of the herd was in order.

Kalili once again took the lead, asking for a show of hands of those with experience drafting legislation, constitutions and other such credentials. This prompted an angry response from at least one participant who didn’t appreciate the implication that those without such credentials need not apply.

As explained later by Zuri Aki, a Makalehua member who had taken the lead in the drafting committee, the various committees were to submit their input to the drafting committee, which would use it (after running it by research and legal subcommittees) to craft the provisions of the constitution.

Given the overarching nature of a preamble to a constitution, the preamble committee was given leave to do its own drafting. Keoni Kuoha, the committee chair, and I proceeded to draft preamble options using the specific input from our committee members.

Right before the last week of the ʻAha, the drafting committee, which included many Makalehua members, set up shop at Richardson Law School for a feverish weekend of drafting. Having obligations at home, I planned to telecommute, working on the preamble via a shared Google document template in which the text from the draft preambles was to be inserted into columns for side-by-side comparison and evaluation against the committee’s list of priorities.

Saturday morning I woke to find my permission to access the document had been denied. As it turned out, another participant had been denied access as well. In an email, Kuoha said the problem resulted from me adding something to the wrong column.

In a subsequent email, Kuoha explained:

Collaborative editing was too confusing, even when some of us were in the same room together. Things kept disappearing and changing in ways no one could account for.

Aki had a more pointed explanation for the problem, which he sent to the preamble committee in an email:

We had about 24 people with access to the document and someone didn’t read instructions (and deleted a whole bunch of stuff)

Kuoha would later blame the confusion on a different member whom he said “doesn’t understand the process.”

Nevertheless, I completed my draft of the preamble, which Kuoha said the rest of the committee seemed to prefer. Nevertheless, the next version of the preamble to come out of the drafting committee, sent via email Sunday evening, bore little resemblance to the draft I had submitted. Once again, there was no mention of independence.

My access to the document may have been restored, but it was at this point that my confidence in the process was shattered.

Above: Carol Lee Kamekona of Maui was one of several to raise objections to a last minute attempt by the ʻAha’s drafting committee to strip pro-independence language from the preamble of the constitution.

The Magical Drafting Committee

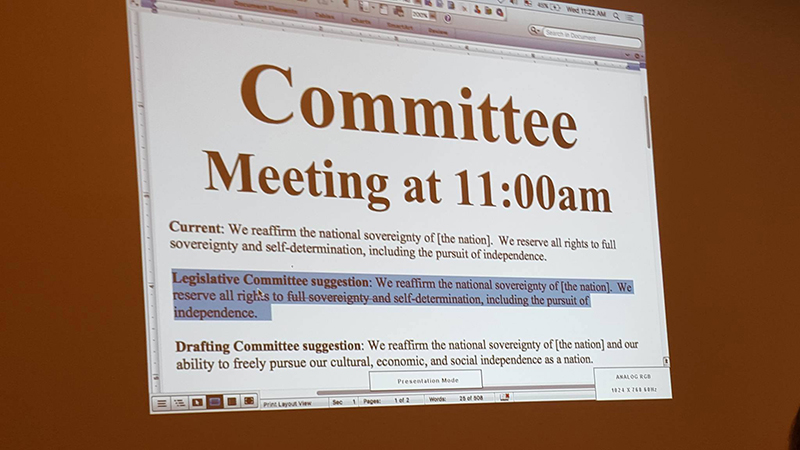

On February 24, preamble committee chair Kuoha called the previously disbanded committee back to the table at 11 a.m. Projecting the latest version of the preamble on a screen, he explained that there had been another change proposed by a different committee. In addition to preamble committee members, the room was packed with members of the drafting committee, which included many members of Makalehua.

This time it was the legislative committee that had put forward changes and, once again, the result was the striking of the phrase “full sovereignty” from the preamble draft.

Members of the preamble committee were outraged. Even those who were in favor of federal recognition chastised the attempt to subvert the committee’s work.

“The Republicans in Congress, they’re trying to take our—any semblance of pono, they’re trying to take that away,” Kuoha tried to explain. “So putting the word ‘independence’ in there, adds to fuel. They’re already walking around with the paper saying, ʻlook at these Hawaiiansʻ right? … So as far as I understand, it’s a political argument … so the impact of their actions could be that we lose benefits.”

Poka Laenui argued for solidly embedding self-determination in the preamble, saying, “The first draft should simply include ʻself-determination as described in international law.’ And that will take care of the missing elements contained in the proposed draft. Then you will not allow the United States to redefine the term ʻsovereignty’ … by international law, sovereignty means full sovereignty. What the United States has done is convert that term into a subsidiary sovereignty, in the same way they treat Native Americans. We should not fall for that.”

Former OHA trustee Moanikeala Akaka wanted answers. “What was the justification for that change?” she demanded. “This is undemocratic to go against the committee!”

Kuoha backpedaled, saying, “We didn’t change anything. It was a major, major political issue that was identified.”

Amidst the hubbub, Lei Kihoi, a former Kanaʻiolowalu commissioner and member of the drafting committee, stepped forward to back the changes.

“This is just a democratic process. I’m one of the drafters and what we do is—it’s not possible to get the true intent of your committee. So we’ll draft something and and the process is, it goes back to you and you tell us what you want. It’s not carved in stone … We can’t be in all the committees so we have to kind of guess what you guys are doing. So we’ll draft and draft. I’ve written laws, written constitutions … so it’s important for you to tell us what you want.

… We’re doing the best we can.”

Above: The original contentious preamble language next to the suggestions from the legislative and drafting committees.

“Who gave drafting committee the right to take out everybody’s wordings that they have fought for, for a week and a half? Who gave the drafting committee that kuleana? None of us here. None of us,” said Carol Lee Kamekona, from Maui, as applause broke out in the room. “So now that means we only have one day as plenary to go over everything that every single committee has talked about and we have to approve that supposedly by tomorrow? Hewa.”

Preamble Committee member Lori Buchanan of Molokai, sister of Walter Ritte, was also critical of the process by which the drafts went back and forth between preamble and draft committee.

“I have a procedure matter… It should have went: preamble, draft, draft preamble, preamble, draft,” said Buchanan. “Take it to the plenary. Let everybody decide. Then we can come down and hash this out. Because when [the constitution] come out, of course we’re going to have to.”

Even staunch federal recognition supporters were upset by the last minute changes:

“I did not want ʻindependence’ in [the preamble] at this time, so I did dissent,” said Kahiolani Papalimu, a participant from Hawaiʻi island. “However, over the next few days, and in conferring with others and hearing that it is possible to include that and still leave the way open for both, I’m fine with it. But when [the preamble] comes back and it’s so different, I feel like I should have stayed at the pool all week … We thought we was all done, amazing, and so we ran to other committees, and I see it being done [in those committees] too. Their hard work that’s going to this magical drafting committee is coming back missing tons of stuff.”

Fred Cachola, a kupuna from Hawaiʻi island, was also adamantly opposed to the drafting committee’s unwarranted changes.

“It did have all the manaʻo we could have after three days of discussions. And if this meeting is now going to overrule and change … everything that this committee put into it, I don’t think that is pono,” said Cachola. “I dearly would love to know, who among the drafting committee decided to change … I’d like to have those people here and say, ʻwe, in the drafting committee decided to use this because…’”

Overwhelmed by the opposition, Kuoha deleted the offending legislature committee suggestion from the screen. But it was too late for some. The impression of an undemocratic process was inescapable.

With just one more day to go, the notion of fairness and balance at the ʻAha had all but been dissolved.