Sovereignty pains

The journey toward self-determination for Native Hawaiians does not come without its own form of growing pains.

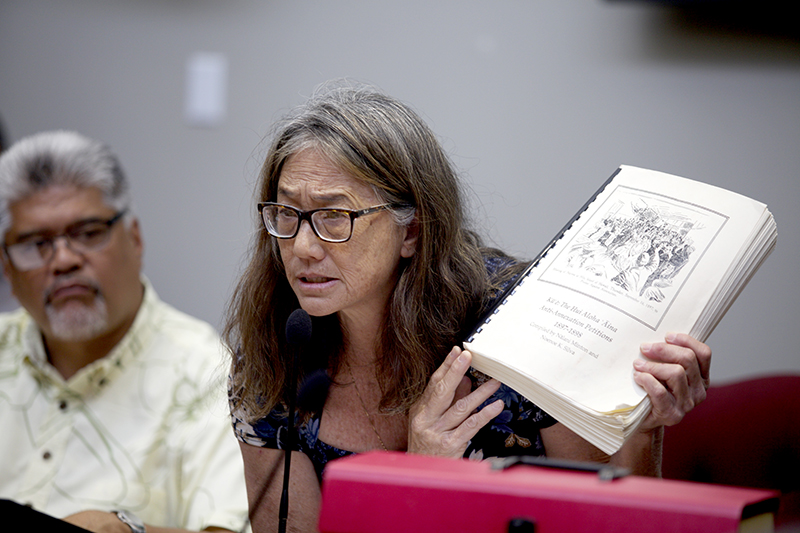

Above: Clare Apana advocates for a catalog of eligible Hawaiian voters based on the Kūʻē Petitions rather than Kanaʻiolowalu. | Will Caron

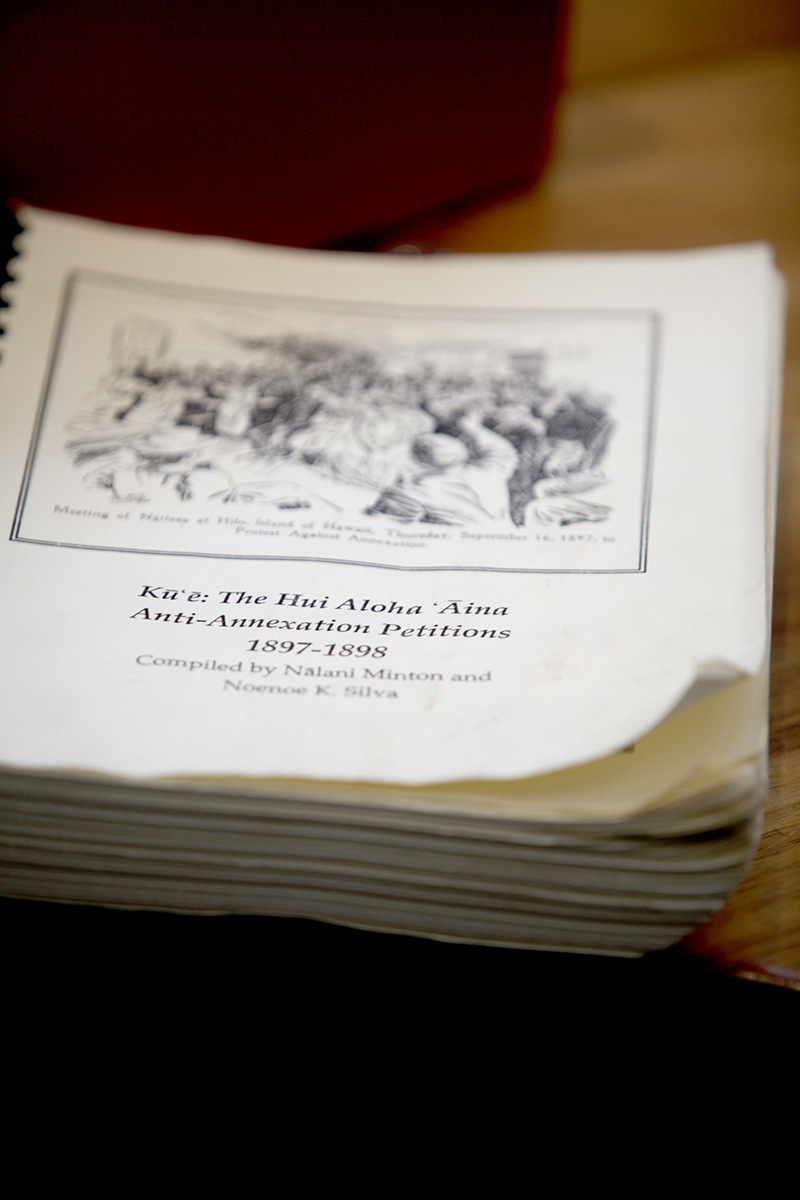

Clare Apana of Wailuku, Maui, and her sister Cyndi, have been working on creating a database of Native Hawaiians based off of the names of their ancestors on the 1897 Kūʻē Petitions. The petitions are proof that the Hawaiian community—the lāhui—did not accept the overthrow of their monarchy and the seizure of their kingdom. Apana’s project could advance the Hawaiian Sovereignty cause by creating a catalog of the entire modern lāhui that can be used to form the basis for a new, democratically elected Hawaiian government; a list that is completely independent of the U.S government and the State of Hawaiʻi.

“We have gone to every single moku on the island of Maui and we would like to continue that by visiting every single moku on every other island as well,” Apana told the audience at the April 23 meeting at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA). “We will continue to work on this until every member of the lāhui is able to join with their kūpuna. And when they do, the tears flow. They say, ‘This is my kūpuna, and I want to sign with them.’ That’s how we discover the true lāhui.”

Efforts to figure out what a Hawaiian government would look like, who is eligible to vote for it, and how it could be created have been ongoing since the Hawaiian cultural renaissance of the 1970s. It was out of that cultural awakening that OHA itself was born, created during the 1978 Constitutional Convention. In more recent years, OHA, the State of Hawaiʻi, and Hawaiian stakeholders have gone through several, varied attempts at moving the process forward, but the journey toward self-determination has not come without growing pains.

“If you’ve talked to any of your constituents, I’m sure you’ve heard: no one trusts this process, and it has gone very astray,” said Apana, referencing the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission’s own list, Kanaʻiolowalu. “Before we give you our list, we have to be certain that these names—the names of our kūpuna—will be used in the right way, in an honest way, in a way that is pono. Because we are bringing forth a history that has not been previously recorded and we are making it accessible to our people, and to archive and protect that history so that the truth about Hawaiʻi can be known. The people on this petition are the greatest resource that we have to show who makes up the lāhui.”

Above: Close up of the Kūʻē Petitions. | Will Caron

The problem with Kanaʻiolowalu

“At this point Kanaʻiolowalu is the property of the State of Hawaiʻi; it does not belong to us,” commented OHA trustee Peter Apo. And therein lies the main problem many Hawaiians have with Kanaʻiolowalu, and with its predecessor, Kau Inoa.

In an interview conducted with kanaka maoli and member of The Red Nation David Maile, he talks about “radical” forms of resistance to colonialism. What he means is resistance from outside the pre-existing, dominant, state system, which constantly subverts efforts toward true self-determination in order to maintain its power. Kanaʻiolowalu (and Kau Inoa before it) is a State of Hawaiʻi-sponsored effort, in concert with the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) and is, therefore, neither radical nor helpful.

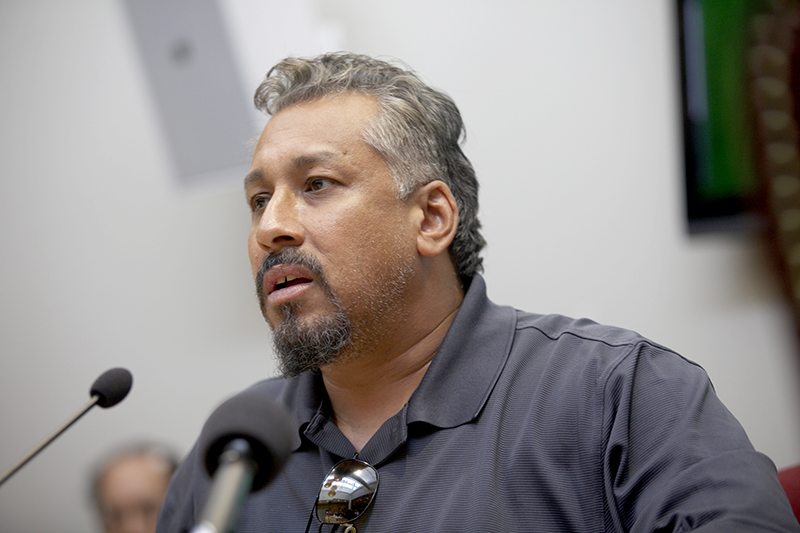

“As trustee Apo said today, Kanaʻiolowalu is the property of the State of Hawaiʻi; do you guys know what that means?” activist Andre Perez of Movement for Aloha No ka ʻĀina (MANA) asked at last week’s meeting. “We should know the implications of that term, roll, and the historical legal precedent of native rolls coming out of the Dawes Act. I’ve been saying for a long time now that we need to look at the implications that a roll has for our lāhui. Because state legislation is not true self-determination; it’s not self-determination unless it comes from the people.”

Above: Andre Perez made the connection between the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission and the Dawes Commission of the 19th century, which contributed to the displacement of Native Americans from their land. | Will Caron

The Dawes Act of 1887 authorized the president of the United States to survey American Indian tribal land and divide it into allotments for individual purchase by Native Americans. Those who accepted the allotments would be granted United States citizenship. The stated objective of the Dawes Act was to stimulate assimilation of Indians into mainstream American society. Individual ownership of land in the European-American model was seen as an essential step. But the act also provided what the government would classify as “excess” Indian reservation lands remaining after allotments which could be sold on the open market to non-Native Americans.

The Dawes Commission registered Native Americans in what became known as the Dawes Rolls. The Curtis Act of 1898 completed the process by which the federal government no longer recognized tribal governments and abolished tribal communal jurisdiction of Indian land. During the ensuing decades, Native Americans suffered extreme dispossession of lands and other social ills. In recognition of this failure, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the U.S. Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, ending allotment and reaffirming the right of Native Americans to organize and form their own governments.

“I had two Kanaʻiolowalu trustees tell me at a different hearing that it’s not a real roll,” said Perez. “So I called the U.S. Department of the Interior and I asked them: ‘Is Kanaʻiolowalu a roll or not? Because their commissioners are telling me it’s not.’ And the response that I got was, ‘[We] find that very disturbing, because the Department of the Interior only deals with rolls.’ Kanaʻiolowalu is a native roll.”

In May of 2014, political scientist Keanu Sai provided OHA staff and trustees with a memorandum based off a letter that OHA Chief Executive Officer Kamanaʻopono Crabbe sent to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry earlier that same month. In that letter, Crabbe voiced his concern that carrying out the directive OHA was given in 1978 by the State of Hawaiʻi might be a violation of international law, unless it can be proven that the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi no longer exists. The letter went unanswered.

“There is no evidence to show that this is the State of Hawaiʻi; this is the Hawaiian Kingdom!” said attorney Dexter Kaiama to resounding shouts of “Ēo!” “To support and fund Kanaʻiolowalu is a direct violation of international law, and the board of trustees is responsible by taking money that belongs to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. Based on the staff presentation to the board concerning Kanaʻiolowalu, I can only conclude that they have either failed to address, or continue to deliberately ignore the information provided to them in that memorandum.”

Above: Ekini Lindsey of Waimea, Hawaiʻi Island, shares her genealogy with the trustees. She is related to both trustee Hulu Lindsey and OHA chair Bob Lindsey. | Will Caron

Growing pains

Self-determination has always been an integral part of OHA’s purpose. Governance is a priority within OHA’s strategic plan, which describes an eventual transfer of assets from OHA to a Native Hawaiian governing body which, of course, requires that such a government exist. The latest attempt involves a new entity called Naʻi Aupuni (“To Reclaim the Kingdom”), which would act as an active facilitator during the three thus-far outlined stages of the nation-building process:

1. An election, in which Hawaiians could decide whether or not to govern themselves and choose from candidates that emerge from the Hawaiian community.

2. An ʻaha convention, in which those Hawaiian delegates elected by their peers will convene for the purpose of bringing the new government to life and determining what relationship the governing entity would have with the Hawaiian community.

3. A referendum, in which the Hawaiian community chooses whether or not to ratify the governing document created by the elected members of the Hawaiian government.

“Naʻi Aupuni is an independent organization made up of unpaid, volunteer board members from the Hawaiian community,” said President and Director Kūhiō Asam. “We exist solely to establish a path to Hawaiian self-determination in the most transparent manner possible. It is a path that is open to all Hawaiians who choose to participate in this very important decision-making process. We have no predetermined, expected outcome for this process of nation-building for Hawaiians. We, as directors, have committed that we will not run as delegates, and neither will those with whom we contract. We will remain neutral on this path.”

But Naʻi Aupuni comes with problems, according to Hawaiian stakeholders, including the fact that, right now, it appears to rely heavily on Kanaʻiolowalu. Another issue has to do with the fact that the process through which Naʻi Aupuni was created, despite Asam’s claims, has been less-than-transparent.

On November 7, 2013, OHA trustees adopted amendment language offered by then-trustee, now-chair Robert Lindsey that stated that, if there were to be a convening of Native Hawaiians for the purpose of self-determination, that the appropriate role for OHA would be as a facilitator, a neutral convener.

On December 19, 2013, the trustees voted to form an ad-hoc committee on governance-planning, the purpose of which was to come up with a proposal for the next step toward self-determination, establishing an active facilitator to lead the lāhui toward the three nation-building steps.

On March 6, 2014, the trustees reviewed a statement of commitment that came from the ad-hoc committee on governance-planning. The commitment was that OHA would partner with other Native Hawaiian organizations, especially aliʻi trust organizations and Hawaiian civic clubs. The trustees voted to fulfill this commitment.

OHA staff then began working to fulfill the vision laid out by the committee by consulting with the lāhui and the aliʻi trust organizations. OHA staff did door-to-door canvassing, held more than 20 community meetings across the archipelago and three governance summits. OHA staff held meetings with the executives of the aliʻi trust organizations, including on neighbor islands.

By June, 2014, a number of these groups had decided to hold a convening amongst themselves to discuss whether they felt they could take on the responsibility of facilitating a nation-building process and, if so, what that would look like. Those discussions continued for the remainder of 2014.

“The original model that we had proposed was based off the aliʻi trusts and royal societies,” said Crabbe. “Unfortunately, we did not get commitments from many aliʻi trusts. We were left with just a few organizations willing to participate: the Lunalilo Trust, Hale o Na Aliʻi and ʻAhahui Kaʻahumanu and, at one point, the Royal Order of Kamehameha. At one point the group wanted to move forward on its own and we respected their autonomy as a group.”

Those organizations still left decided to accept the responsibility, but did so by forming a separate, stand-alone entity: Naʻi Aupuni. But even though Naʻi Aupuni was born from the discussions between these aliʻi trust organizations, it is a separate entity and, therefore, the four individuals chosen to lead that entity no longer speak for the original aliʻi organizations. And that’s problematic for stakeholders, including the OHA trustees themselves, who were expecting something more democratic.

Above: Walter Ritte tells the OHA trustees that he is very wary of handing over the reins of self-determination to Naʻi Aupuni. | Will Caron

“We spent many, many hours in this room and took up a lot of OHA’s time trying to figure out how we were going to bring everyone together to build our nation,” said activist Walter Ritte. “Now, today, we find out there really is no aliʻi trust involved with any of this. For some strange reason, the aliʻi trusts could not organize themselves, but they are going to try and organize the Hawaiian nation. This doesn’t make any sense whatsoever.

“I am totally opposed to this idea of giving four individuals the reins and letting them steer our canoe,” continued Ritte. “I’ve never seen these people involved in the efforts over the years to build our nation. Somehow, before we strike this deal, we need to clean this up, because we can’t build our nation in the sand. We need a solid foundation, but this is not the foundation that we were told would represent us.”

“I find it disturbing that we’re considering giving Naʻi Aupuni $2.8 million when we don’t even know who they are,” agreed Perez. “Who is Naʻi Aupuni? Who are those four individuals? Can somebody tell me? Somebody tell me their names. I know Kūhiō Asam because he introduced himself to me, but who are the other three?”

Perez’s question was not rhetorical; he actually wanted to know, and CEO Crabbe did his best to answer the question, but even he could not remember the last name of one of the four Naʻi Aupuni directors.

“OK, so we’re going to give $2.8 million to four people that even the CEO doesn’t know all of them?” Perez asked, incredulous. “How’s about you guys gives that $2.8 million to me, Kaleikoa (Kaʻeo), Skippy (Ioane) and Dexter (Kaiama)? Sounds absurd, right? I think it’s absurd that you’re giving that kind of money to four people you can’t even name.”

“I’m concerned because the trustees approved the process that was presented to us by Ka Pohana Crabbe, and that was that the aliʻi organizations would be in this position, rather than four individuals,” agreed trustee Hulu Lindsey. “[Pohana] explained a process that [the aliʻi organizations] were excited about, but as soon as they were told this was going to be a Kanaʻiolowalu list thing, the Royal Order of Kamehameha backed out. So, in this case, the aliʻi organizations felt there would be some kind of liability in listing their organizations in support.”

Above: Clare Apana brandishes a hard copy of the Kūʻē Petitions, which she is using to create an independent list of Hawaiians. | Will Caron

According to Asam, Naʻi Aupuni’s relationship to Kanaʻiolowalu is not one of dependence, but one of inclusion.

“We understand that many Hawaiians are on a list that verifies them as Hawaiian, and that many have chosen not to be on that list,” said Asam. “Naʻi Aupuni is exploring options that include additional eligible Hawaiians. We encourage all Hawaiians to be on our list, so that they may participate in the election or run as a delegate. All who choose to participate must be able to verify that they are Hawaiian.”

According to OHA staff, the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission has committed to sharing its data with Naʻi Aupuni if it is requested. The commitment is that those Hawaiians who have chosen to be verified through the Roll Commission’s Kanaʻiolowalu process will not be excluded from Naʻi Aupuni’s list.

But that may or may not be true. “I had a beneficiary of mine from Maui call you because she had another possible solution for how we can bring in those people that didn’t want to sign the Kanaʻiolowalu list and you told her that wasn’t possible, that you folks were going to go with Kanaʻiolowalu,” countered trustee Hulu Lindsey. “I’ve always advocated for another way for our people to participate in this ʻaha, not only from the Kanaʻiolowalu list, but from any other list.”

“To clarify, the Kanaʻiolowalu list, in our contract, is simply one that will not be excluded,” said Asam. “Naʻi Aupuni, as an organization, is looking at many options to include other eligible Hawaiians. We would like to expand the list beyond Kanaʻiolowalu and are exploring possibilities to make that happen.”

As it turns out, that Maui beneficiary that called Asam was present at the meeting: it was Clare Apana, and she was calling about her Kūʻē Petitions project.

“How dare you,” she said to Asam. “When I asked you how we could be a part of this as descendants of those on the Kūʻē Petitions, you said that you had no place for us, unless we wanted to run the ʻaha. I do not want to come to any convention under Kanaʻiolowalu; I want to come under the Kūʻē Petitions. How will you include us, the descendants of the petitioners, the kānaka maoli?”

Aliʻi Leighton Tseu, of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, advocates in favor of using Apana’s list rather than Kanaʻiolowalu. | Will Caron

And while Naʻi Aupuni is asking OHA to borrow $2.8 million to fund their active facilitation of the self-determination process, Apana is asking for a measly $25,000 to continue her and her sister’s project. And based on the testimony at the meeting Thursday, it sounds like most stakeholders would much rather sign the Kūʻē Petitions list than Kanaʻiolowalu.

“If Kanaʻiolowalu was pono, like Kaleikoa (Kaʻeo) has been saying since day one, Hawaiians would be coming out of the hills to sign up,” said Perez. “But we all know that didn’t happen. We all know.”

A member of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, Aliʻi Leighton Tseu, agreed: “The Royal Order of Kamehameha I was established April 11, 1865, by Kamehameha the V to honor the legacy of Kamehameha the Great,” said Tseu. “We find it very important that the lāhui understand and uphold the values of our kūpuna. Our order stands for five things: First, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi still exists; second, we will preserve and protect the ancient chiefly customs and traditions of Hawaiʻi; third, we formally recognize the Kūʻē Petitions; fourth, we will not support legislation that divides our people; and fifth, we will always uphold the truth of what happened to our nation, and ensure that no further harm falls upon our kingdom.

“We speak from our naʻau because that’s where our kūpuna’s wisdom comes from. You follow your naʻau and you follow the truth.” said Tseu. “The truth will always surface; it may not be today, but it’s coming.”

“We know who we are, just like [our kūpuna] knew who they were,” said Apana. “It’s not just for those who are living; it’s also for those who have already gone, so that they know we are still alive, and we are bringing back our country.”