Solidarity between Hawaii, Okinawa on U.S. militarism

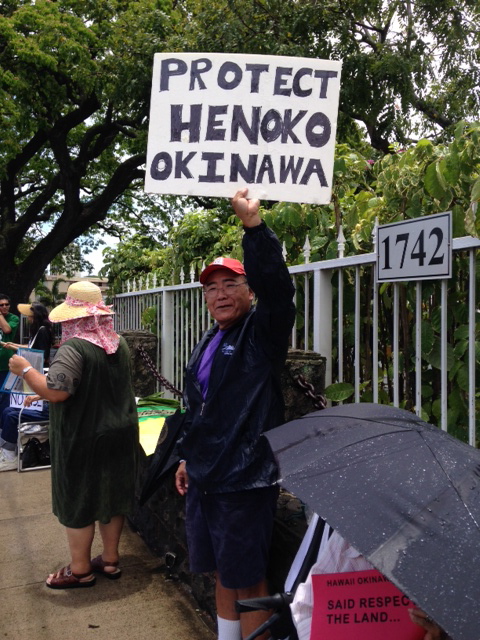

Last week, protestors of another planned U.S. military base in Okinawa rallied outside the Japanese embassy in a show of solidarity with Hawaiians and other occupied indigenous peoples around the world.

Above: A replacement facility for the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station at Futenma is planned in this stretch of sea off Henoko, Okinawa Prefecture. | KYODO

Last week Wednesday, April 29, while much of our attention was focused on the following day’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs meeting dealing with the Defend Mauna Kea movement and the Thirty-Meter Telescope protests, another important example of United States colonialism was also being protested against. About a dozen people came out for an impromptu rally for Okinawa and Hawaiʻi in protest of U.S. military bases on both archipelagos.

“Weʻre here out of kuleana; out of Aloha ʻĀina for Okinawa, for Hawaiʻi, for the honor of our ancestors, as well as for future generations,” said progressive public educator, peace activist, musician and community organizer Pete Shimazaki Doktor. “Hawaiʻi and Okinawa have such similarities, including that both are island nations still occupied by their colonizers, still sustaining disrespect and disregard by their respective national governments. We must unite along with other indigenous peoples oppressed by similar military occupations worldwide in our collective efforts for justice, peace and self-determination.”

The rally was a peaceful event and was attended by three people that served in the U.S. military, including uncle Don Matsuda, 91, who served in the 442nd during WWII, and who has been advocating for peace and against the destructiveness and futility of war ever since he returned from the front.

Attendees tied ti leaf to the fence of the Japanese embassy—a symbol of solidarity between the sacredness of the pristine, life-sustaining waters around Okinawa’s Henoko community (where the U.S. and Japanese governments plan to build a new naval base) and Hawaiʻi’s Mauna Kea, which currently “hosts” a large military training facility (Pōhakuloa) at its base, given ti leafʻs use in spiritual and medicinal cleansing. Ultimately, it was a symbol of Aloha ʻĀina or, in Okinawan sensibility, nuchi du takara: “that all life is a treasure to be cherished and sustained for future generations of life.”

The Tuesday before the rally, four Japanese governmental representatives, including a member of Japan’s National Diet from Okinawa, spoke at the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (UHM) about the on-going plight of the Okinawan people and their ʻāina under the joint military alliance of Japan and the United States. The speakers made an appeal for solidarity between the people of Okinawa and Hawaiʻi, both lacking recognition by their respective national political leadership.

It was standing room only at the UHM talks, and attendees expressed hearing the kāhea (“call”) for kuleana (“responsibility”) on this issue. Doktor stood before the crowd and said he was going to picket at the Japanese consulate on Wednesday at noon, and invited others to come as an exercise of kuleana.

Both the talk and the rally addressed the building of yet another base in Okinawa, which has already been forced to sacrifice 20 percent of the land on its largest island to U.S. military bases. A whopping 74 percent of U.S. military forces in Japan are concentrated on the tiny islands of Okinawa, despite the fact that the archipelago only consists of 0.6 percent of Japan’s overall landmass.

Both Japan and the U.S. are pushing for a military port to be built on the reef area of the Henoko coastal district of Nago, northern Okinawa Island. The base would replace the current facility at Futenma, also on Okinawa’s main island. But protestors insist that the coastal area near Henoko is an important source of food for the neighboring communities of Henoko and Takae, and that the area also contains endangered species including dugong.

Approximately 80 percent of the Okinawan people (in votes and polls) oppose the expansion of U.S. military bases in Okinawa. Okinawan municipal and prefectural officials have also come out strongly against the construction and/or expansion of additional bases. In February of 2015, Okinawa Govenor Takeshi Onaga said he is considering using his powers to order a suspension of the Japanse Defense Ministry’s preparations for construction of the new base.

“I will use every means to fulfill my campaign pledge,” Onaga said during a news conference, referring to his commitment during the gubernatorial election to block the U.S. base’s construction. But Onaga’s actions have pitted him against the Abe Administration in Tokyo, which has been pushing hard for the Futenma base to relocate to Henoko.

“Elected officials are not representing the will of the people, thus the people have to raise our voices and defend our communities from militarism,” said Doktor. “From Henoko to Mauna Kea, Jeju to West Papua, Tibet to Guam, and so on: indigenous peoples are answering the kāhea worldwide—and we are united.”