Selling sex in paradise

Prostitution is a diverse, thriving industry in Honolulu, but misinformation about the highly varied nature of sex trafficking makes it harder to change laws that could provide protection to victims.

Doug Upp remembers the first time he had sex for money. It was in the early 1990s, and he was skating around Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles. A van started following him, and the driver asked if he needed a ride. He declined.

“So I went and skated to the next corner, and there he is again,” says Upp. The man asked if Upp was sure that he didn’t want a ride.

“He’s all, ‘Are you sure? I’ll give you money.’ And I was like, ‘Money? What, you owe me money?” explains Upp. “‘For what?’”

The man replied that he wanted to perform oral sex on Upp, who agreed and got in the van. He’s been dabbling in the sex industry ever since.

“Growing up, I thought everybody [in the sex industry] was living a terrible time on the streets, and some people were. But a lot of people weren’t,” says Upp.

Upp, who has since started video production company Shaka Zine, worked as an independent sex provider and, briefly, in a bathhouse. He says that his experiences working in the sex trade were positive, and that he was in control of every situation he put himself in.

“I don’t have a pimp. I keep all my own money. I make all my own decisions,” he says. “If I don’t want to do something, I don’t do it, in every situation.”

But Upp says that his experience in the sex trade is only one out of many. “Everybody has a completely different experience with it. There’s no single story.”

Sex Trade Diversity

Because of the cultural taboo and legal ramifications associated with prostitution, there is little information on the frequency and nature of sex work. Upp adds that, because the sex industry is so private, there’s no way to know who is involved with the sex trade or how they are buying and selling sex.

“There is no way, really, to know the numbers,” agrees Reverend Pam Vessels. “When you think about sex work, you have to think about it in a bigger context than just what you’re seeing. If you don’t, you’re going to be deceived.”

Vessels worked as a public health outreach worker in Waikiki for 10 years and founded Hāle Hoʻomaka Nā Wāhine, a transitional facility for women trying to exit the sex industry. She says that the life of a sex worker varies greatly. Some work every night on the street, while other independent sex providers like Upp may only see one or two clients per month.

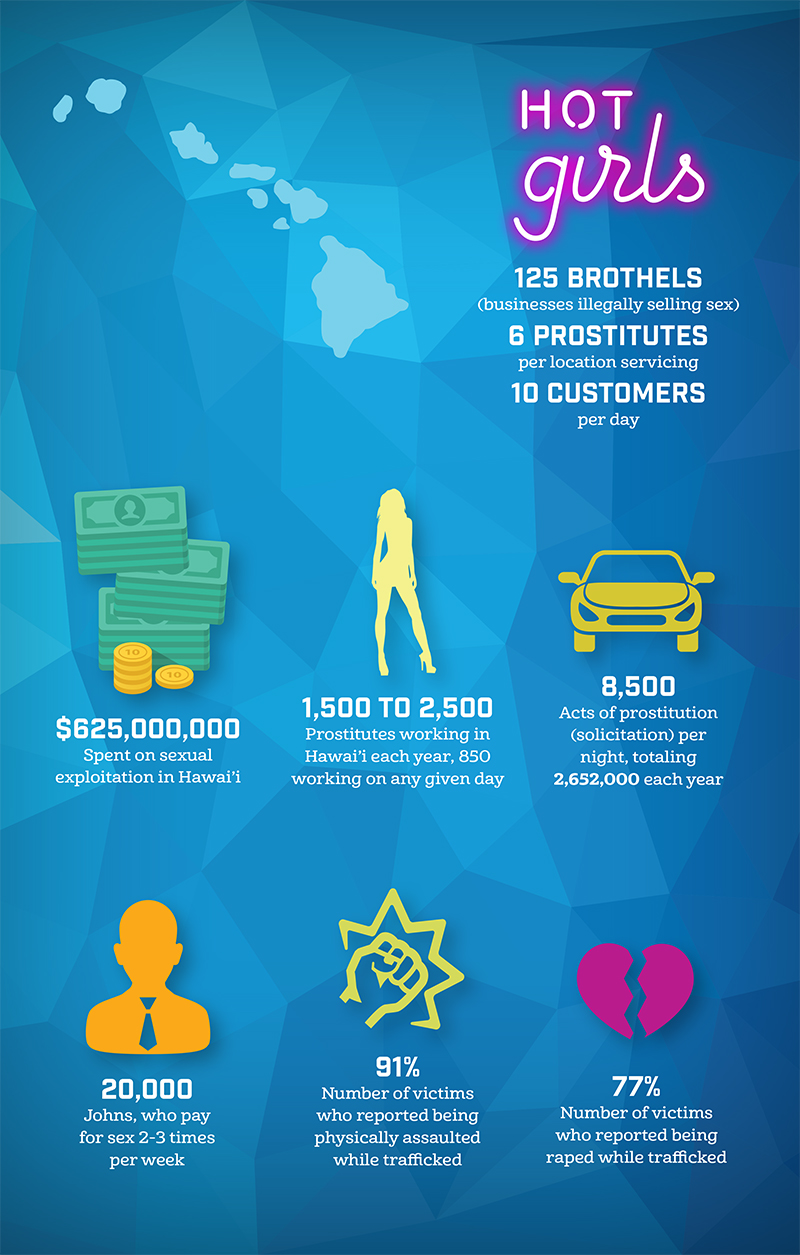

Although Vessels worked predominantly with street prostitutes in Waikiki and Chinatown, she thinks street prostitution is actually only a small fraction of the entire commercial sex industry. According to a recent study by the IMUAlliance, an estimated 2,652,000 acts of prostitution resulting from some form of solicitation are committed in Hawaii each year (8,500 per night).

“A lot of the queens are on the street … The boys are mostly not on the street,” agrees Upp. “But just because I do it doesn’t mean that I know everybody or know everything that’s going on.”

Working as an advocate for those in the industry, Vessels has met a variety of people who sell sex: from women who are controlled by pimps to others with Ph.Ds, who work with a select group of clients only.

“If you see or know or have interactions with a woman who’s a really high-end call girl in New York City, then that’s what you’re going to think about prostitution,” Vessels says. “If you meet a woman, or two or three women, who work in brothels, and that’s all they’ve ever done, then that’s what you’re going to know.”

Upp, who is mostly familiar with the male sex industry, says he feels that the discussion should include all forms of prostitution, not just female, street-based prostitution.

“There’s other people there … [Members of the public] don’t talk about anything but this poor female,” Upp says. “And it’s good to talk about them—we want to help people. But don’t assume that everybody’s [the same] … There are people that are in sex work against their will, or they were manipulated somehow to think that whatever they’re doing they want to do. But that’s not everybody.”

“Any time someone talks to you about sex work, you need to think … Where are they coming from?” stresses Vessels.

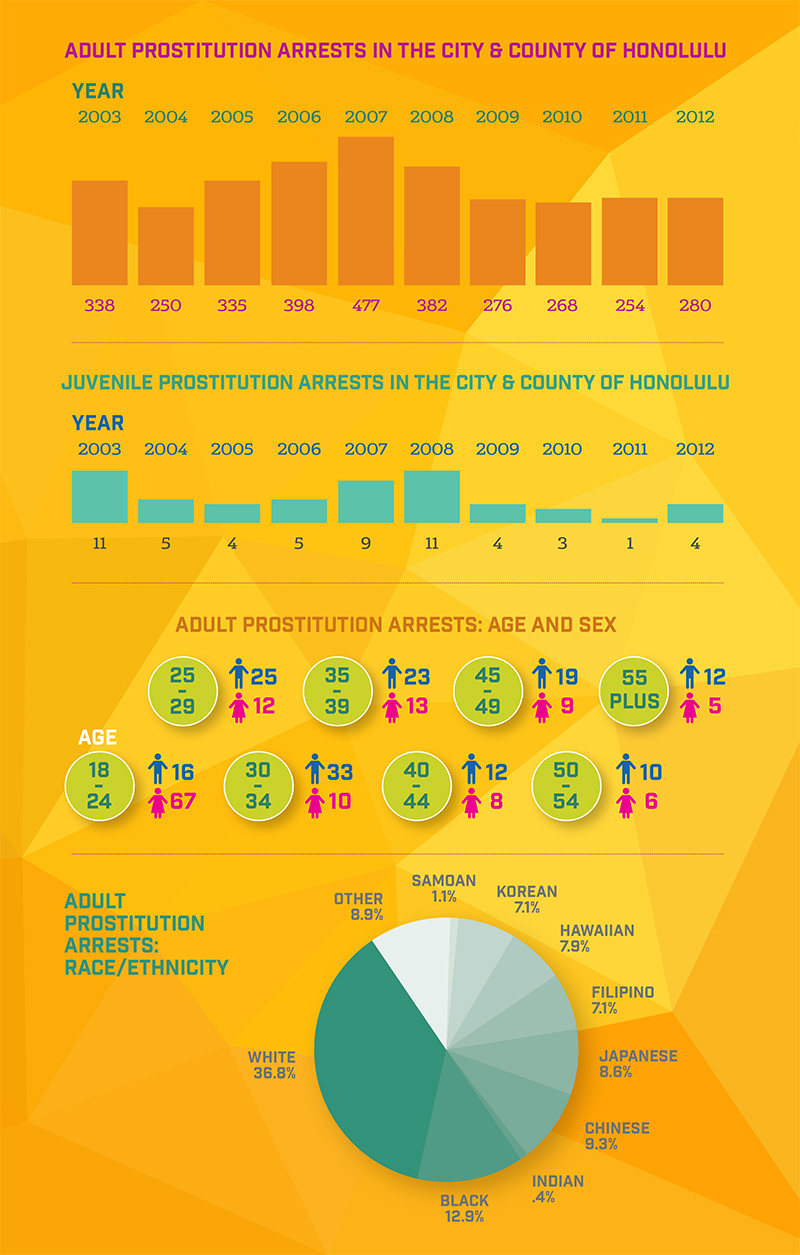

Source: IMUAlliance | Graphic by Mae Ariola

Visible Prostitution

Vessels says that the commercial sex industry is booming in Honolulu. Research conducted by IMUAlliance puts a low-ball estimate of the amount of money spent on prostitution and other forms of sexual exploitation, annually, at $625 million.

On any given night, an estimated 850 sex workers are soliciting acts of prostitution in Honolulu. Sex is sold in a variety of markets, from hostess bars to online advertisements. But it is the women who walk the streets of Waikiki and Chinatown who are the most visible.

According to Alika Campbell, Program Coordinator of Hale Kipa Youth Outreach (YO!), the downtown prostitution industry includes everything from pimp-controlled women to private sex contractors working for drug money.

“The [women] on the streets—very consistently—are not age appropriate to YO!; most of the visible prostitutes are over the age of 22,” Campbell says. It’s estimated that, at most, fewer than 30 percent of visible prostitutes are under 22.

Campbell adds that, in his experience, hardly any of the women working the streets in Waikiki are minors. He says that if minors were to engage in prostitution, it would almost certainly be in a private place where there is far less risk of interference from police.

IMUAlliance estimates that, annually, 54 percent of sex workers are underage, however, meaning that Vessels is right to guess that the majority of the sex trade occurs off the streets. The estimated average age of entrance into the sex trade is 13.4-years-old; while the estimated average age of victims is 17.2-years-old.

YO! provides health outreach services such as free condoms to women on the street. The facility also provides meals, clothing, education and health services to homeless and transient youth.

“We see a lot of survival sex … a lot of people just hooking up to get a meal or get a place to stay,” Campbell says of the youth at YO! “None of them are involved in any formalized prostitution.”

Of the women working on the street, most are not from Hawaii, according to Vessels.

“Most came here with someone for the purpose of sex work,” Vessels says.

Source: IMUAlliance | Graphic by Mae Ariola

The Pimps

According to Campbell, most of the women working on the street have a pimp. Vessels agrees that most of the women she’s worked with also had a pimp, but that the relationships between woman and pimp varied greatly.

“A stereotypical image of a pimp is something [the public has] seen on Law and Order SVU or something like that, which is horribly, horribly, wrong,” Kris Coffield, executive director of IMUAlliance says. He says in Hawaii, a pimp can mean anything from a mamasan at a massage parlor to a man that traffics women across nation-wide prostitution circuits.

“A pimp is an interesting thing,” Vessels says. “You’re going to have [instances where] a man and a woman are involved in sex work, where the woman works the street and the man is her spouse, and a person who loves her, and cares for her and is a really nice person. You also find pimps that have a different attitude about it. They’re really hardcore. They’re very abusive, if not physically then emotionally, and sometimes both. It can be extremely dangerous for the women.”

Vessels says that childhood experiences and the age at which women start engaging in sex work often affect their choice to work with or without a pimp in the first place. A woman who chooses to enter the sex trade later on in a more stabilized life is less likely to work with a pimp. Vessels points out that the real problem is not the sex work itself but, rather, violence towards women.

“It is definitely a structural issue,” Coffield says. He says that the coordination of services and support to help at-risk youth would help to prevent teenage girls from entering the sex industry in the first place. He says that most women who engage in sex work were previously victims of abuse and domestic violence from broken homes.

“If you’re in a violent situation, whether you’re a street prostitute or an abused wife, there’s brain damage,” Vessels says. “A lot of the trauma didn’t come from the sex work itself, but from their lives before they became involved in sex work.”

But Vessels says that the greatest threat to women working in the sex industry comes from “tricks,” or the men who buy sex.

“In reality, it’s not pimps who kill prostitutes,” Vessels says. “It’s tricks who kill prostitutes.”

Prostitution, Protection and the Law

Because those working in the sex industry are afraid to go to jail, sex workers are far less likely to report assaults and rapes, putting them at greater risk of harm, says transgender rights activist Tracy Ryan.

“Nobody trusts anybody,” says Ryan. “Because it’s illegal and there’s undercover [police], the ability of these women to work together to protect themselves from abusive johns is undermined.”

Ryan says that it would be helpful for sex workers to be able to develop a community to warn each other about potential clients.

“It’s so clandestine and so private,” Upp says. “There’s not really a community.”

Ryan says that current legislation may criminalize workers in the sex industry, whether they want to be there or not. Additionally, those hoping to leave the sex industry may have difficulty finding jobs if they have previous convictions.

“The biggest problem with our prostitution code… is that it criminalizes both johns and victims,” Coffield agrees.

He says many individuals, and particularly those in the trans-gendered community who face workplace place discrimination, engage in sex work just to get by financially. Coffield recently helped provide services to a young mother who wanted to leave the sex industry. Considering Hawaii’s high cost of housing and comparably low minimum wage, sex work was the only way she could make ends meet as a young, single mother.

“When you live in a state with the highest cost of living in the country, eventually you have to survive,” Coffield says. “And in some cases, prostitution can be a way of simply earning the money necessary to pay bills.”

The current prostitution code in Hawaii criminalizes johns and providers equally, whether or not the provider was engaging in prostitution willingly. Victims of sex trafficking are criminalized under prostitution statutes because there is currently no definition of sex trafficking under Hawaii state law.

“One of the best things that we can do is to take the prostitution law and parse it into two: one that applies to johns, and a much lesser, differentiated, differently-named statute—if we have to have a law—that applies to what we believe to be our victim population,” Coffield says.

Sex trafficking victims receive little protection under Hawaii’s state laws. Over 91 percent of sex trafficking victims are physically assaulted, while 77 percent are raped while being trafficked, according to a recent study by IMUAlliance.

“If we’re unwilling to give those people any rights, then victimization and exploitation become rampant,” says Ryan.

This feature is part 1 of a series of 4 articles covering sex trafficking in Hawaii.