Mauna Kea and the awakening of the lahui

Multiple generations of campaigners are rallying around Mauna Kea as a symbol for the larger issues of self-determination and Aloha ʻĀina in what is becoming one of, if not the, largest mobilizations of Hawaiian activism in decades.

“We have vowed to protect the remnants of our culture, no matter what cost; and the culture cannot exist without the land.” — George Jarrett Helm

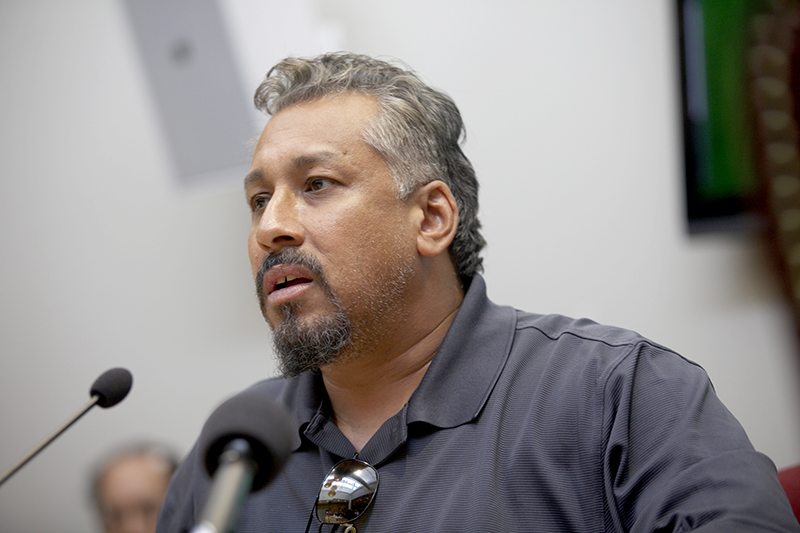

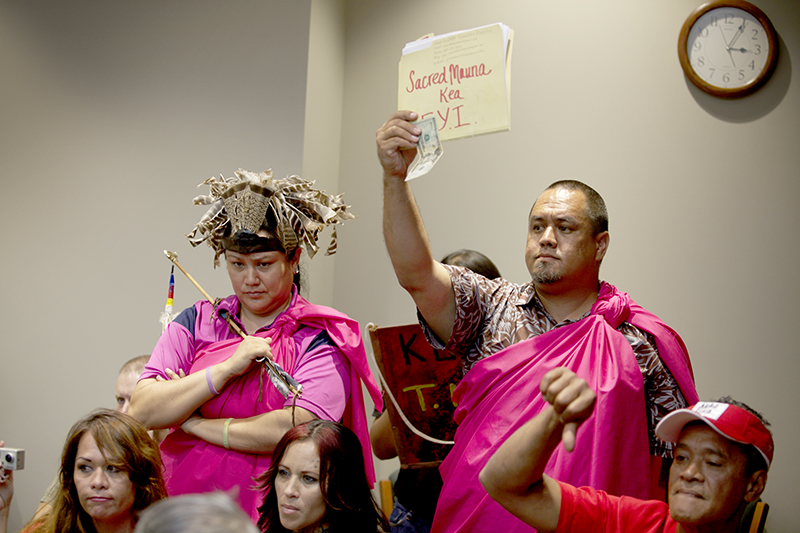

“We are in a time of enlightenment for our people! We have risen; we have awakened; we have remembered; and we’re going to restore ourselves!” thundered activist and Associate Professor at the University of Hawaiʻi (UH)‘s Maui College Kaleikoa Kaʻeo (pictured above, left) at at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA)‘s Thursday, April 23 meeting.

The primary focus of the emotionally charged meeting was to hear testimony on whether or not OHA should rescind its 2009 decision to support the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) project.

“There have been a lot of efforts over the years to unify the Hawaiian people. We spent millions and millions of dollars on [Kanaʻiolowalu],” said activist and Kū Kiaʻi Mauna organizer Kahoʻokahi Kanuha (pictured above, right). “Well guess what? We’ve done that for you. This is the single greatest activation, mobilization and unification of the Hawaiian people since 1897.”

The trustees, conscious of the groundswell of public support for rescinding the 2009 decision, decided to move their decision-making hearing on the matter up to Thursday, April 30, which will allow all the trustees to be present. (Trustees Dan Ahuna and Hulu Lindsey made and seconded the motion to move the date up.)

“Don’t deprive the people of something that we have supposedly been striving to achieve for so many years,” continued Kanuha. “This is what everybody wanted, and we did it with zero dollars. We don’t need money. I’m not here to ask OHA for money, because we’ve shown we can do it without money. I’m here to ask OHA for support.”

Construction of the massive telescope was supposed to start in late March of this year, in spite of ongoing litigation, but campaigners like Kanuha have set up camp on Mauna Kea and, through peaceful civil disobedience, have prevented workers from moving equipment to the summit.

“This movement is something that has opened the eyes of the world,” said activist and fellow Kū Kiaʻi Mauna organizer Lanakila Mangauil. “Being on that mauna and seeing so many young people involved is a beautiful thing. But our cheeks are also soaked with the tears of our kupuna who have come up to give us their blessings.” (Read his full speech here.)

The efforts of these young activists to defend the mountain, which is intrinsically tied to Hawaiian culture and spiritual beliefs, from further development have inspired Hawaiians and their supporters across the state (and around the world) to come together and make a stand for self-determination and for Aloha ʻĀina unlike anything witnessed since the Kahoʻolawe movement of the 1970s; possibly ever.

“No consent, no treaty, no title, no TMT—it’s really that simple,” said Kaʻeo. “And the truth is, the young up there on that mountain? They know all of this. The truth is so powerful, it leads people to do what is necessary; to take the steps necessary to reclaim ourselves as the ʻōiwi, as the kānaka, as the maoli.” (Read his full speech here.)

To which, the majority of those gathered in the OHA board room responded with a resounding, “Ēo!”—“Yes!”

“[Hawaiians] have been silent for many years on a great many things, and we’ve had no opportunity to determine our own futures. Even when public hearings are held, our voices are not heard,” said OHA trustee Rowena Akana. “I think this telescope has given Hawaiians an opportunity to rally around something. If the board rescinded its support for the project, I think the most important thing that would achieve is to show the people that we hear them.”

Trustee Hulu Lindsey, in an emotional speech, recognized the vitality these young activists have brought to the movement: “These ʻōpio that are … that are on our mauna; they’re different,” she said, fighting back tears. “They’re not like how we Hawaiians have been in the last 50 years: screaming and yelling while people just ignore us. These ʻōpio, they’re smart. They are operating in a very humble way … and I believe they are getting the attention of the people that make decisions. So it’s really important that we respect them, respect their movement, and support them.”

Above: Activist Shannon Crivello speaks directly to the OHA trustees | Will Caron

Generations of activism

“I grew up, all my life, listening to each and every one of you share about aloha ʻāina and Native Hawaiian rights,” activist Shannon Crivello told the trustees. “As a nine-year-old, I witnessed the Kahoʻolawe movement of the ‘70s and listened to my uncle George Helm share his manaʻo about aloha ʻāina. I grew up listening to uncle Walter, intrigued by his words, fascinated by the message of these young leaders during the ‘70s, amazed by the movement at that time. I listened to aunty Colette Machado and Joyce Kainoa and saw these strong young women standing there next to the men, fighting along side. I listened to the words that your generation taught me when I was the keiki. And that is the reason why I am here: because of your manaʻo.

“I am proud to be Hawaiian and, in this generation, we need that,” continued Crivello. “It was your generation that brought back the concept of speaking the language, of practicing our culture; your generation was the catalyst for Pūnana Leo, OHA, Merrie Monarch—our culture! I ask you to remember what your own kupuna taught you as Hawaiians: It is our kuleana to mālama this ʻāina, and to be the kānaka that live and practice aloha everyday no matter what. Stand with us.”

As Crivello says, since the Hawaiian cultural renaissance of the 1970s, there has been a concerted effort on the part of Hawaiian activists to re-introduce aspects of their culture into education, the arts, and even government. And that cultural flourishing is what has given this new generation of activists, the young Mauna Kea defenders, such strength and conviction.

“And what did you think was going to happen when our keiki started to learn the truth?” Kanuha asked the trustees. “Did you think they would just learn it from pre-school through the 12th grade and then forget about it? What did we think was going to happen? This is what’s happening! Because we know the truth. We know the truth, and once you learn the truth you can never forget the truth.”

“I am a product of your efforts to re-introduce Hawaiian culture into our education system; mahalo nui. And it is just like bruddah Kahoʻokahi said: Yeah, you basically created these avenues for us, so now you deal with us,” Mangauil told the trustees, eliciting laughter from the room. “We are the products of your prayers; of your sacrifices; of your hard work! We were taught and trained in the traditions of our kupuna, as well as taught to be able to survive in this Western world.”

Above: Activist Andre Perez urges the OHA trustees to rescind their 2009 statement of support for the TMT project. | Will Caron

“It is my belief and understanding that the ʻāina in contention should be preserved in perpetuity as a public benefit, not only for Hawaiians like myself, but as a public benefit for all, as is stated in our state motto and made clear to me by our young Mauna Kea leaders like Lanakila and Kahoʻokahi,” said former OHA trustee Don Aweau. “‘Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono.’ They understand the essence and the mana of those words.”

Brandishing the pamphlet that outlines OHA’s strategic plan, activist Andre Perez of Movement for Aloha No ka ʻĀina (MANA), urged the trustees to pull OHA’s support for the TMT in solidarity with the young activists on the mountain.

“Everything you need to stand with your lāhui and protect sacred Mauna Kea is right here in your own strategic plan,” said Perez. “The language is clear: ‘To work together unified’—so stand with your lāhui. We all know Mauna Kea is a big money issue. So my question for you folks is, when do we, as Hawaiians, draw a line in the sand and say no more? I ask you to follow us, your lāhui; to stand with us and protect Mauna Kea.”

Attorney Dexter Kaiama has led the legal battle in recent years arguing against the lawfulness of the State of Hawaiʻi and, just last week, sent a cease and desist letter to the TMT corporation on the grounds that they have no legal contract to build the telescope. He reiterated what Kaʻeo said: “No treaty, no title, no TMT.”

“The State of Hawaiʻi does not lawfully exist and, therefore, cannot enter into any lawful contracts with the TMT,” said Kaiama. “Because [the TMT LLC] does not have any lawful entity to deal with, their construction of the telescope on Mauna Kea is destruction of property in direct violation of international law.”

Kaiama’s wife, Manu, herself a prominent activist, disputed the claim that the 13 already existing telescopes went up without any resistance from the Hawaiian community, and that Hawaiian activists have only now “discovered” their desire to defend their culture.

“I also find it very presumptuous for those in favor of the telescope to claim to know what our ancestors would have said about this scientific exploration 100 years ago,” she said. “How do they know? How dare they be so presumptuous as to say that our aliʻi would have supported this project?”

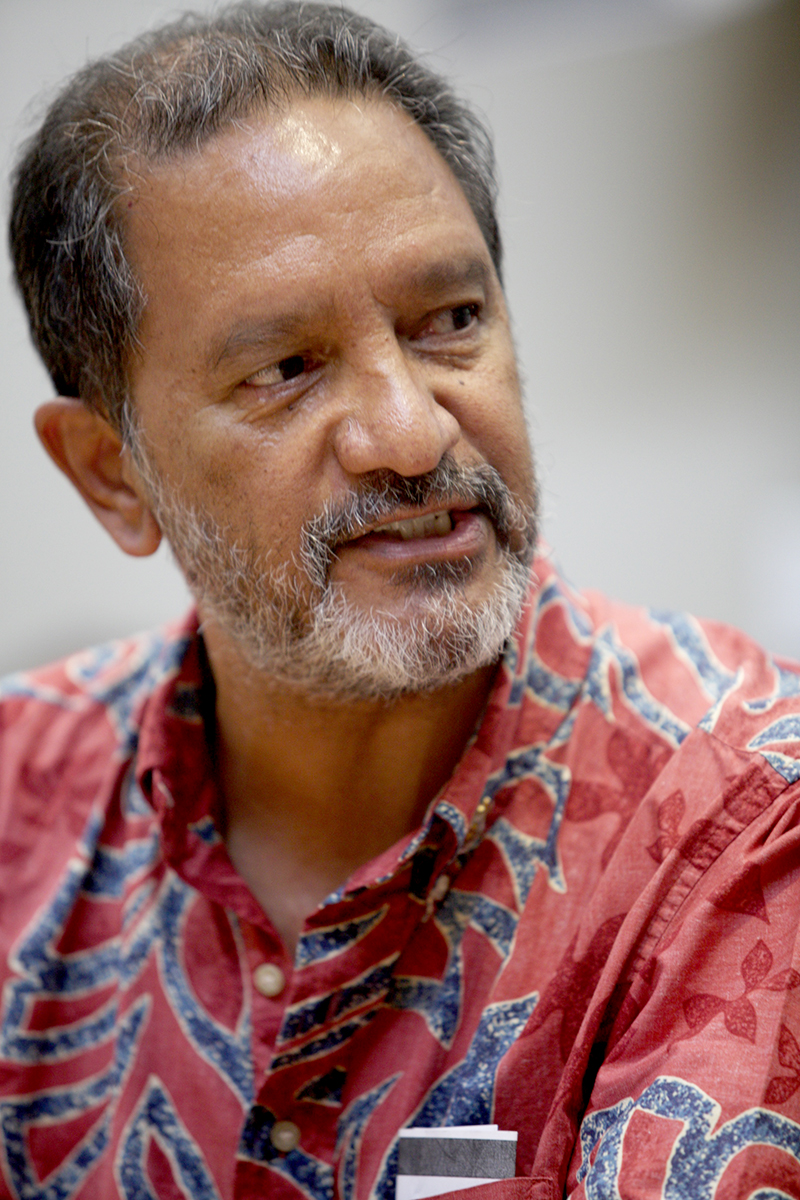

Above: Activist Kaleikoa Kaʻeo gives a passionate speech at Thursday’s meeting. | Will Caron

Arguments for the TMT

For their part, TMT supporters made their standard arguments: the project is a vital educational and economic resource that will both bring humanity closer to an understanding of the cosmos and inspire the youth of Hawaiʻi to pursue new research that has the potential to benefit all mankind.

“I want to explain something about the nature of discovery: we don’t always know what the payoffs will be, we can’t always pinpoint what the specific benefits to mankind will be,” said Professor Geoffrey Mathews from the UH Mānoa astronomy department. “For example, when the mathematical description of how light works was first figured out by Hertz, it wasn’t until after his death that the patent for the radio was made. That technology depends on that understanding of how light works. When that understanding was first worked out, no one had any idea that it would lead to a device that would allow us to communicate instantaneously with people on the other side of the planet. Without the act of discovery, we don’t even know what we’re missing.”

Wallace Ishibashi Jr., a Hawaiian Homes Commissioner (East Hawaiʻi) since 2013, brought up the need for jobs and a diversified economy on Hawaiʻi Island, something that was echoed by Big Island farmer Richard Ha. (The TMT would only provide 140 full-time jobs once construction is over, according to the project’s website.)

Others delved heavily into the realm of scare tactics. UH Institute of Astronomy professor Richard Wainscoat, for example, claimed that, without the TMT, the world would be at risk of being struck by a devastating asteroid that we would be unable to see coming until it’s too late.

Ishibashi claimed that children are being bullied in schools because their parents support the TMT, and that protesters on the mountain are harassing Hawaiian workers on the TMT project who are just trying to make a living.

“Mob mentality rules right now: ‘either you are with us, or you are against us; if you’re not Hawaiian, we will get you,’” Ishibashi said. “What will it take; somebody gotta die? What will it take before you realize that what you’re doing on the mauna is wrong?”

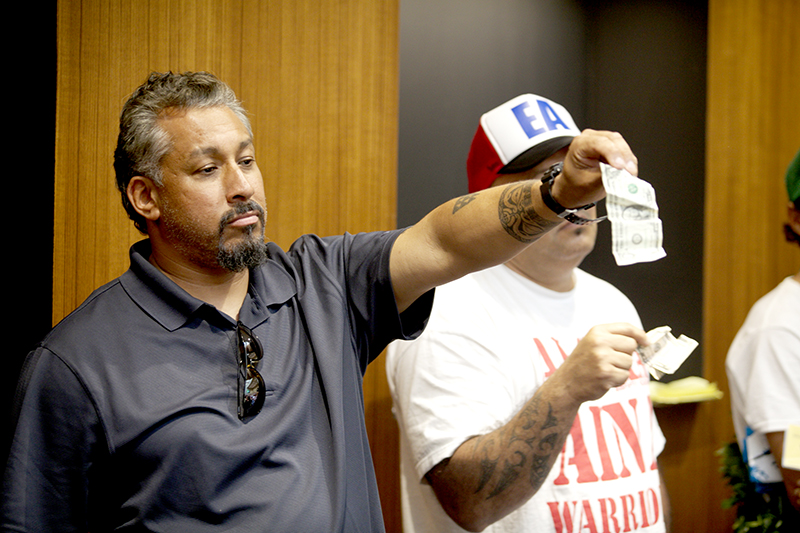

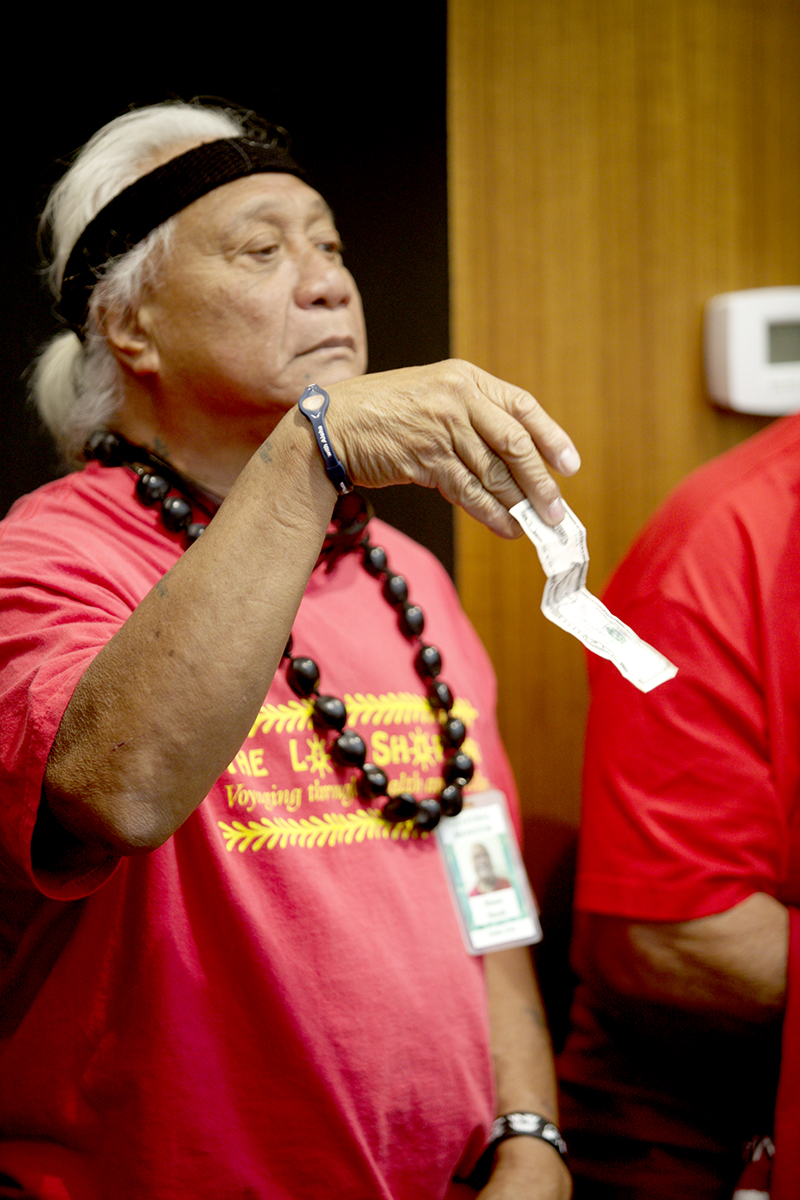

Above: Mauna Kea supporters and activists held up money during Wallace Ishibashi Jr.‘s testimony in silent protest of his statements. | Will Caron

“I’ve been on the mountain every day and every night, and saying that those of us on the mountain have been disrespectful, harassing TMT employees, threatening them—that’s an absolute lie, and [Mr. Ishibashi] knows it,” countered Kanuha. “I can show you a video of someone else being threatening; I can show you a video of someone else being disrespectful—swearing at us, cussing at us, shoulder-bumping us. Everybody here has watched the videos; we’re not hiding anything. From my estimation, we’ve conducted ourselves in a very pono way, and we have shown great respect to those who oppose our stance. Watch the videos of the arrests: how many people yelling; how many people screaming; how many people getting violent? Zero.”

“How we have conducted ourselves on the mauna, of all things, is what has called attention to us,” agreed Mangauil. “The world is watching how we conduct our Kapu Aloha. Thousands and thousands of people have already visited the mauna in just these few weeks. We have spoken to hundreds of visitors to our islands who have come up the mauna; and we talk with them, we educate them. We’ve comforted kupuna who have come up the mauna, but can do little more than cry. We comfort them because we know that they went through their suffering for us; we are the products of your prayers.”

“When the head of the ATSD (Advanced Technology Solar Telescope) solar observatory on Maui came to our school about eight years ago, I sat right across from him and I asked this person—his name is Craig Foltz, of the National Science Foundation—and I asked him directly: ‘What is the humanity of this project?” said Kaʻeo. “You tell me. As a Hawaiian, I can take the pain, I can bleed if it’s going to save some lives—tell me what it is.’ And he looked me directly in my eyes and said: ‘It’s just pure selfish research.’ That is the honest truth. Pure. Selfish. Research.”

“In October, at the groundbreaking ceremony for the TMT, I had a similar opportunity as Kaleikoa did to discuss this issue with a scientist,” said Kanuha. “I asked him to tell me, as a person of this land who won’t be directly making use of this telescope—just as a regular person—what will be the benefit to us? His answer was simply, ‘curiosity.’ Since when did curiosity supercede the values and traditions in the Moʻolelo of the people of this land? Since when did curiosity supercede sacredness, moʻokūʻauhau, kupuna, ʻāina, that which has sustained us for thousands of years and that will—if we treat it properly— sustain us for thousands more?”

Rallying point

“The debate over the TMT has become confused as the tipping point for Hawaiian Sovereignty,” Ishibashi said. “Local, national and social media have been flooded with impassioned cries that portray Liliʻoukalani as the reason for opposing the TMT, which now symbolizes the United States’ overthrow, the illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the subjugation of its people. Continued support for the illegal actions of protesters on the mountain is a far cry from Kapu Aloha.”

But, listening to the multiple generations of activists that showed up to testify against the TMT, it was clear that the issue has not been confused for anything. It is, in fact, straightforward and clear that the fight to defend Mauna Kea—while just one example in a long history of resistance and struggle—is such a powerful symbol for that resistance that it has empowered the Hawaiian community, the lāhui, to take a stand on the larger issues of self-determination and of Aloha ʻĀina.

As trustee Peter Apo said: “This is about more than just the mountain.”

Above: Activist Kahoʻokahi Kanuha has spent the past month on Mauna Kea as part of the Kapu Aloha. | Will Caron

“The great Gandhi himself said: ‘One of the seven sins is science without humanity,’” said Kaʻeo.

“Science should not come at the expense of our people, our culture, or our history,” agreed Aweau.

“Yet, this is not a movement of anti-science—come on, we’re Hawaiian,” said Kanuha. “We got here because of science. Our kupuna were some of the greatest scientists in the world, traveling the largest ocean on the planet at a time when most people thought the world was flat, scared to sail five miles off shore for fear of falling off the edge. That’s one of the greatest achievements in the history of mankind. Think about that—they did that on canoes, with stone and wood, not metal telescopes. We had courage and faith in the teachings of our ancestors. When did our ancestors teach us to desecrate ʻāina?

“When Captain Cook first came in 1778, he couldn’t believe how productive the lands were, couldn’t believe how clean the people were, couldn’t believe how we could feed and sustain a people so easily,” continued Kanuha. “More than 800 fish ponds in Hawaiʻi; is that not science? Thousands and thousands of loʻi; is that not science? Look at the Kumulipo; that’s science. What we’re against is desecration. What we’re against is the further dehumanization of our people that’s been institutionalized since 1896 when they banned Hawaiian in public schools.”

Above: Activist Lanakila Mangauil speaks of his generation’s world view; one that holds the value of Aloha ʻĀina above all else. | Will Caron

“We are starting to look at our world in a different way,” said Mangauil. “The idea of progress is much different for many in our generation. We’ve been blessed with the opportunity to learn our ʻāina, how the land actually works, and to put it first. What the generation before has called progress, I call suicide.

“Humanity needs something else right now,” continued Mangauil. “More tangents and more distractions that cause us to look even farther away from our kuleana right here is not what we need right now. Going up there and searching the universe? Maybe one day, when we’ve earned the right to. You say we need to be looking for a new planet and a new home; I say, if we cannot even take care of this one, then we don’t deserve it.

“If we can teach ourselves to be loyal to our home, to take care of our environment as our kupuna did; to become intricate parts of our environment—not an outside entity acting on and corrupting our environment, but an actual part of our environment—then we may actually earn that right,” said Mangauil. “But until that day: wrong mountain, wrong time, wrong people.”

Kū Kiaʻi Mauna

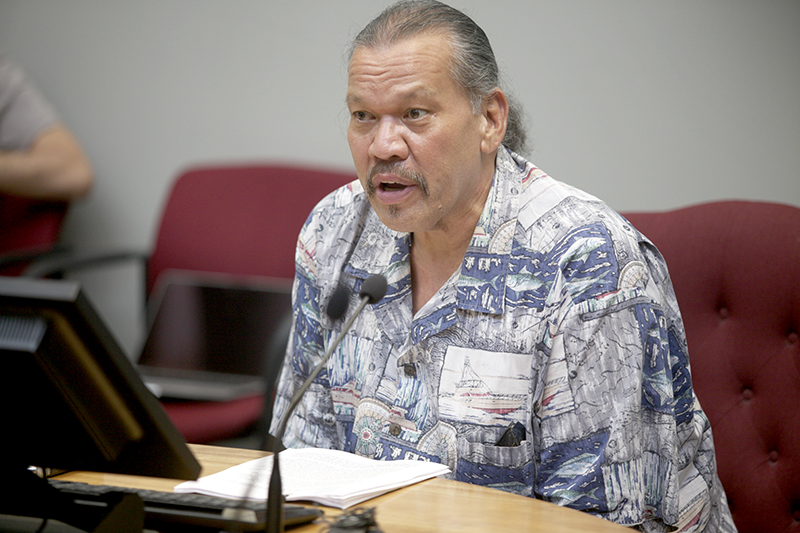

Above: Uncle Walter Ritte was one of the “Kaho‘olawe Nine,” a group of activists who landed on the island of Kaho‘olawe in January 1976 in opposition to the military bombing that was then taking place on the island. | Will Caron

Above: Kaleikoa Ka‘eo and Andre Perez sit across from Uncle Walter discussing their game plan before Thursday’s meeting. | Will Caron

Above: Ka‘eo listens to a TMT-supporter’s reasoning outside the OHA board room. | Will Caron

Above: Ka‘eo then tries to explain the view point of the Mauna Kea defenders to the TMT-supporter. | Will Caron

Above: Kamahana Kealoha debates the TMT issue with Günther Hasinger, director of the Hawai‘i Institute of Astronomy. | Will Caron

Above: Former OHA trustee Don Aweau stands in line to sign up to testify at Thursday’s meeting. | Will Caron

Above: Kū Kiaʻi Mauna supporters wore red and yellow shirts to Thursday’s hearing. | Will Caron

Above: One Kū Kiaʻi Mauna supporter brought his daughter to make the point that even the very young members of the lāhui are aware of this issue. | Will Caron

Above: OHA trustees Dan Ahuna (left) and Chair Bob Lindsey (right) shake hands before Thursday’s meeting. | Will Caron

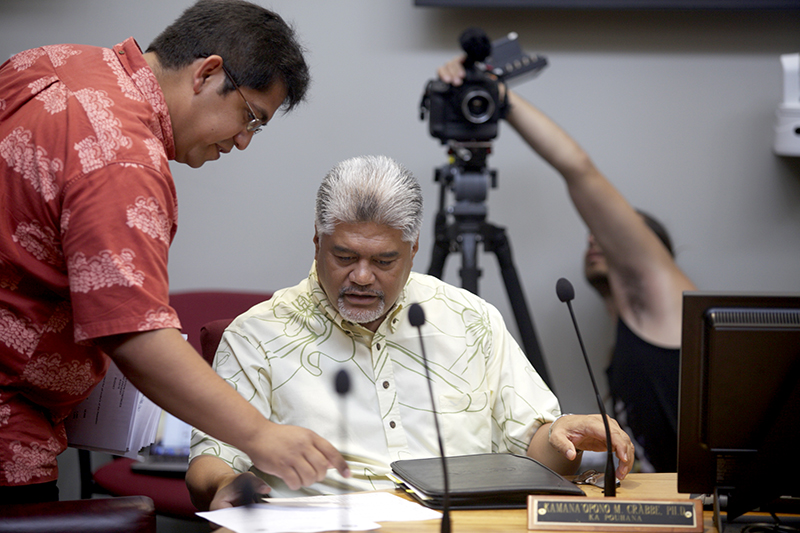

Above: OHA Chief Executive Officer Kamanaʻopono Crabbe reviews his notes before Thursday’s meeting. | Will Caron

Above: OHA trustees Hulu Lindsey (left) and Peter Apo (right) listen to testimony at Thursday’s meeting. | Will Caron

Above: OHA trustee Rowena Akana said, at Thursday’s meeting, that although OHA, as an organization, has yet to throw its support behind the Kū Kiaʻi Mauna movement, individual trustees have. Based on trustee statements at the meeting, trustees Akana, Ahuna and Hulu Lindsey are in full support; trustee Apo seems to be on the fence; and trustees Bob Lindsey and John Waiheʻe are unknown.

Above: Last summer, OHA trustee Bob Lindsey (now the chair) pushed for OHA to remove itself from a Department of Land and Natural Resources contested case regarding the TMT. He told the Independent that his reasoning was based off the majority of testimony he heard then. Given that the majority of testimony on Thursday was in support of Kū Kiaʻi Mauna, we would expect him to now vote to rescind OHA support for the telescope, based on that logic. | Will Caron

Above: OHA trustee John D. Waiheʻe IV, son of former governor John D. Waiheʻe III, was first elected to the board in 2000. | Will Caron

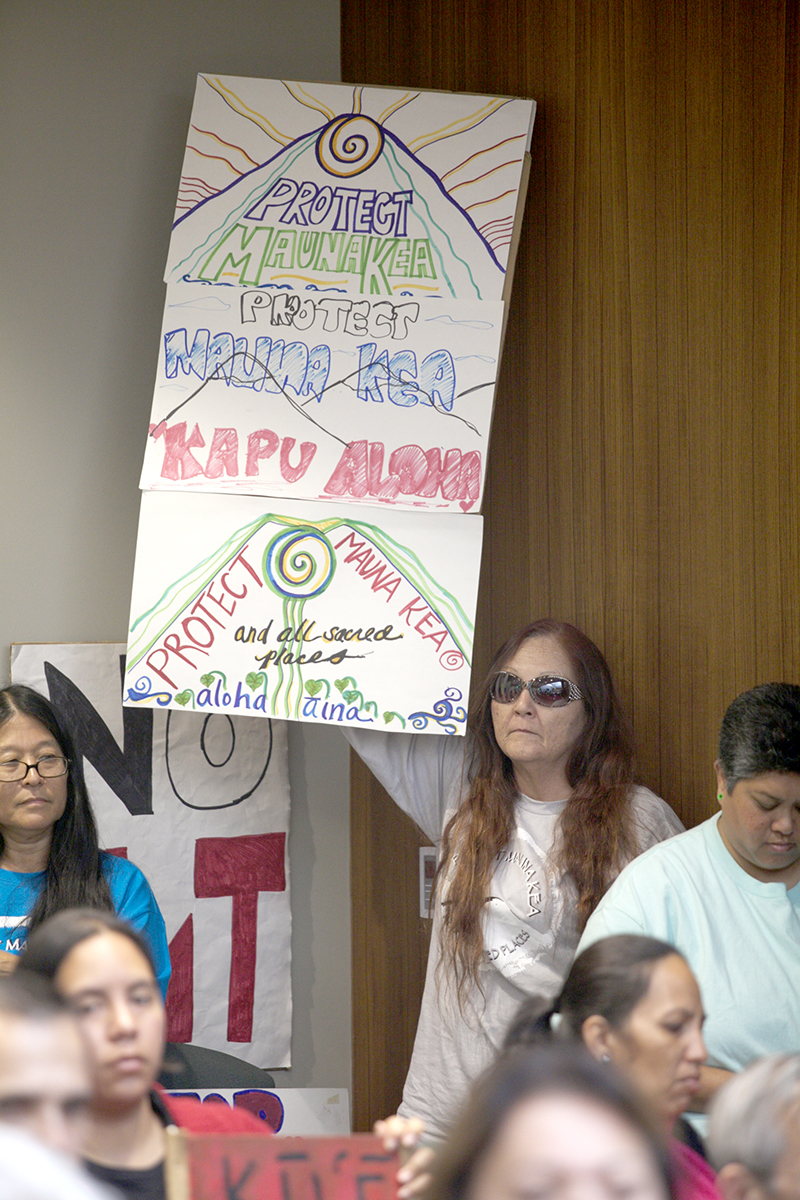

Above: Kū Kiaʻi Mauna supporters brought signs and held them up during pro-TMT testimony. | Will Caron

Above: OHA CEO Kamanaʻopono Crabbe listens attentively to Kaleikoa Ka‘eo’s testimony. The CEO sat next to each of the testifiers and appeared to agree with many of the statements made by Kū Kiaʻi Mauna supporters. | Will Caron

Above: Ka‘eo’s testimony was stirring, resulting in shouts of “Ēo!” and “ʻAe!” from the majority of the people in the room. | Will Caron

Above: Andre Perez calls the OHA trustees’ attention to their own strategic plan in urging them to support Kū Kiaʻi Mauna. | Will Caron

Above: Hawaiian Homes Commissioner Wallace Ishibashi Jr. was one of only a few Hawaiians who testified in support of the TMT project. | Will Caron

Above: Ishibashi’s testimony centered around the financial benefit the telescope would provide. Kū Kiaʻi Mauna supporters in the audience held up whatever money they had in their wallets in protest. | Will Caron

Above: Günther Hasinger of the Institute of Astronomy at UH also tried to convince the OHA trustees that the TMT would be a major economic boon for Hawaiʻi, stating that astronomy was a completely harmless industry. | Will Caron

Above: Hasinger’s statements were also met by silent protest from the audience. | Will Caron

Above: Big Island farmer Richard Ha, of Hamakua Springs, argued that revenue from the TMT could help Hawaiʻi weather the eventual collapse of the fossil fuel industry. | Will Caron

Above: Attorney Dexter Kaiama argued that the TMT LLC has no legal contract to build its telescope because the State of Hawaiʻi is an illegal and illegitimate entity under international law. | Will Caron

Above: Manu Kaiama pointed out, contrary to claims that the aliʻi would have supported the TMT, that the modern day aliʻi who have spoken about the TMT have come out against it. | Will Caron

Above: Former OHA trustee Don Aweau ended his testimony by chanting “Kū Kiaʻi Mauna!” The audience quickly joined in and soon the OHA board room was filled with the sound of Hawaiians chanting the slogan, “Kū Kiaʻi Mauna!”—“Stand strong in defense of the mountain!” | Will Caron