Lanakila Mangauil and the foundation for kapu aloha

Part two of our profile on Joshua Lanakila Mangauil examines the origins of the kapu aloha, a Hawaiian philosophy of non-violence and respect that the Mauna Kea defenders are using to deflect development advances on the sacred mountain.

Photo: Photo: Lanakila Mangauil (center) marches at the Aloha ʻĀina Unity rally on August 9, 2015 | The Hawaii Independent Staff

The next time I sat down with Lanakila Mangauil was May 20, 2015. By this time, the movement to save Mauna Kea from the Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT) had become a global one.

The mass arrests that took place on April 2 had jolted national and international media out of the kind of complacency so often shown with respect to reporting on indigenous issues in Hawaiʻi. The drama of these arrests was also a catalyst for garnering support from Hollywood. Aquaman movie star Jason Momoa’s superhero-sized “We Are Mauna Kea” Instagram campaign had cascaded and spread to other actors, as well as to recording artists and professional athletes.

During the six weeks since the arrests, no one else had been jailed, and support for the blockade continued to grow around the globe. On April 22, after camping out at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ (OHA) Nimitz Highway headquarters, Mauna Kea protectors had marched en masse to the TMT corporation’s downtown office and, from there, to the state capitol. One week later, on April 30, OHA rescinded its prior support for the TMT project after hearing hours of testimony from Hawaiian activists and their supporters.

Within this whirlwind of activity, Mangauil was difficult to track down; he spent most of his time in meetings and at community presentations promoting Hawaiian cultural values and educating anyone who would listen about the importance of protecting Mauna Kea.

For years, Mangauil had been promoting traditional Hawaiian culture in Hāmākua through the E Ola Mau I Ka Pono summer program. For the past two years he’d been developing and fundraising for the establishment of a Hawaiian Cultural Center in Hāmākua that would function as a year-round home for the teaching of Hawaiian arts, crafts, history, philosophy and methods of community service.

At the same time, he was preparing to take Hawaiian culture across the planet to Poland, along with fellow Mauna Kea protectors Hāwane Rios, Ruth Aloua and Deynna Kaʻiulani Honi Pahio, for the annual Lokahi Honua cultural exchange program. The highlight of the program was to be the inaugural “Aloha Festiwal Polska,” where Hawaiian cultural traditions like hula would be complemented by film screenings and concerts.

It was in the midst of preparations for all of this, fresh from a presentation on Mauna Kea at Kealakehe High School in Kailua-Kona, that Mangauil returned to the mauna.

Since our last interview, the Kūkiaʻi Mauna village had been reduced to a single, large tent lined with lawn chairs and cots. A Hawaiian Kingdom flag flew atop the tent, side-by-side with a Mohawk Nation flag—The Mohawk Unity Flag—that had been sent across the Pacific as a symbol of solidarity by Mohawk Mauna Kea supporters on the mainland.

The large carport tent, which used to house tables and abundant stocks of food and bottled water, had been disassembled and dispersed among the homes and garages of five different protectors “down below.” Just a few of clutches of protectors remained on vigil. The kiʻi (carved figure) of the war god Kū that once stood guard at the entrance to the Mauna Kea Visitors Center was nowhere to be seen.

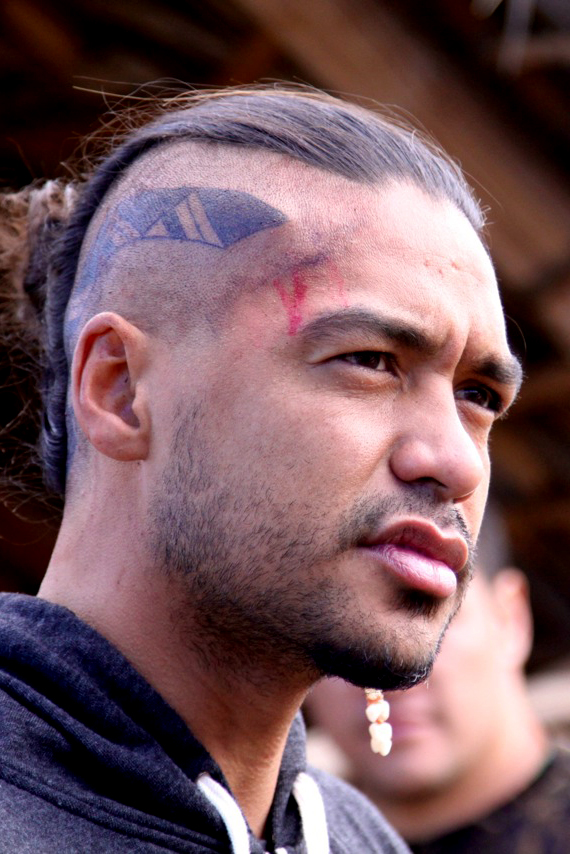

The handy line of lawn chairs, where we sat during our first meeting, had been removed, so my rental car—parked along the Mauna Kea Access Road—would serve as the setting for our second interview. As I fussed with my recorder and laptop, Mangauil scrutinized his coiffure in the rearview mirror. He had just had his head partially shaved Mohawk-style, just as it was on the day he crashed the TMT groundbreaking ceremony, and would later undergo the pain of kākau (tattooing) on his head in the shade of the still-standing hale pili.

It was nearly noon and the sun was so warm that, before we even sat down, we had to crack open the doors to jettison some of the air that had been trapped and heated inside the car. In the interest of time, I hint that I’m looking for brief answers this go round. Mangauil has his own rhythm though, and proceeds to launch into a 10-minute explanation of “kapu aloha”—the code of conduct espoused by the Mauna Kea protectors.

Lanakila Mangauil with tattoo | Dominique Jacot

Kapu Aloha

When the notion of “kapu aloha” first penetrated the public imagination in the earliest days of the TMT blockade, critics were skeptical of its origins in traditional Hawaiian cultural practice. Mangauil and other Mauna Kea protectors found themselves on the defensive from semantic sticklers, stuck on the commonly held interpretation of the word “kapu” as “forbidden” or “no trespassing.”

“For myself, kapu aloha is not necessarily a new thing,” says Mangauil. “When I was in Kanu o ka ʻĀina [the Hawaiian Public Charter School Mangauil attended in Honokaʻa], whenever we had ceremonies and stuff, Uncle Nalei [Kahakalau] always used to talk about kapu aloha. Basically, for us in school, it meant no cussing, no swearing, no talking about bad kinds of things.”

The ethic, he adds, relating to how one conducts oneself and relates to others, was especially important when going into traditional ceremony.

For many years, it was also a practice taught by Pua Case, another of Mangauil’s most influential kumus.

“It was something that she always reiterated too,” he says. “Kapu aloha was just a reminder of how to conduct ourselves … particularly in the sense of how we engage in a sacred area—in a space—so to bring consciousness to us.”

Nevertheless, Mangauil says, many have questioned the origins of the phrase and its authenticity “like it’s a brand new thing.”

He adds, “Well maybe it kinda is. But it wasn’t necessarily started by myself, or up here. It has a history. A lot of people have been scrutinizing us with this kapu aloha, saying it’s not real or traditional. And I said, ʻwell aren’t you glad that we made it up then?’”

The idea that something can’t be legitimate unless it’s in a book is alien to Mangauil.

“Culture is a living thing,” he says. “Everything that we learn about in the book, at one point, was created by our kūpuna. And we’ve always been creating new things. Just because there’s been this lull in time where we weren’t allowed to [practice our culture], doesn’t mean that, even today, we can’t still be us as kānaka and create what we feel is necessary.”

It was one of the most revered Kumu Hula living today, renowned scholar and author Pualani Kanakaʻole Kanahele, PhD, who silenced whatever doubts Mangauil might have had.

“Aunty Pua actually said there is an ʻoli—a chant—that speaks of kapu aloha.”

Mangauil acknowledges the traditions of others, quoting the ʻōlelo noʻeau [proverb] “ʻAʻohe pau ka ʻike ka hālau hoʻokahi” (Not all knowledge is learned in one school), but also knows exactly what “kapu aloha” means to him.

“If I had to interpret the word ‘kapu,’ I look at it as a sacred law,” he says. “It’s not just like a kānāwai [law]—it’s not just like a law by man—it’s one that’s linked to the gods; it’s linked to spiritual practice.”

Another criticism of kapu aloha has come from those who say that, when push comes to shove, a more physical kūʻe [resistance] will be required to stop the TMT. But Mangauil takes a different tack.

“Right now, we need to make sure that we are holding ourselves in a pono fashion,” he says. “In reality, any point where you feel you have to [resort to a physical] fight like that—well then that means that we have failed in the process.”

It might seem counterintuitive, but Mangauil maintains the view that a non-violent stance requires greater strength than one that embraces violence as an option. As a teacher, this was an important concept to impart to his students.

“I say [to my students], ʻIn a situation where someone is yelling at you or insulting you or something like that, it’s easier to just lash back out at them, to call them out, to swing your fist, or to pull the trigger. But what if, instead, you hold yourself; compose yourself in a higher manner and listen to what they’re saying?’” says Mangauil.

“Often, we just move with our reactions. Someone yells at you, so you snap back at them. My view of that is that a stronger person will take the harder road. Other people think that fists or insults or that kind of thing are stronger. In fact, those tactics actually show your weakness.”

Furthermore, he says, an opponent faced with “kapu aloha” will often find themselves disarmed.

Perhaps nothing represents this concept better than the iconic photo from the arrests on April 2 showing one officer, nose-to-nose, embracing a kūpuna protector.

“The opponent cannot read you, cannot understand what’s going to throw you off,” says Mangauil. “We’re not going to allow them to see our weakness. We cannot allow ourselves to fall short and succumb to our weaknesses. It’s deep, this kapu aloha. It’s a lot, and it’s not easy. That’s why I think it’s a strong path to take.”

Another Type of Battle

Mangauil exudes a contemplative, philosophical manner. But, when I put the question to him directly, he pokes fun at such “Thinking Man” notions, instead characterizing himself as “philosophidal”—a deliberate mispronunciation of the word—and “just falling short of an instigator.”

Nevertheless, his favorite ʻōlelo noʻeau (Hawaiian proverb)—He aliʻi ka ʻāina. He kauā ke kanaka, meaning “The land is a chief. Man is the servant”—betokens more grounded motivations and fundamental principles of mālama ʻāina.

Looking back again to the day of the mass arrests provides another perspective on Mangauilʻs leadership.

He relates how, the Monday before the arrests, the protectors got a preview of what was to come when they successfully forced TMT construction crews to back down, holding them off for eight straight hours before they turned around and headed back down the mountain.

“I had talked with [Hawaiʻi Police Captain] Sherlock, and he and I were in open dialogue. He told me what they were going to do.”

But once the arrests actually began, the protectors found themselves on “a whole new playing field,” according to Mangauil.

“I was having flashes in my head of every battle movie you can think of; and it was a battle. They were coming for us. Geronimo really came into my mind. The story of what happened to the Apache people when the cavalry came in and everything, too. They were pushed and so they went to their mountains.”

Moving among the protectors, Mangauil called out directions as the police officers moved in.

“I was running back and forth like, ‘Set a line; set a line back here. Make sure that you guys hold it as long as you can. Don’t be confrontational, but do what you can, as much as you can, to hold ‘em off. Hold ‘em down.’”

For six hours, he says, they were able to hold the officers off as they slowly moved backwards, zig-zagging their way up the mountain. Watching the blockade lines from up above, he could see opposing reinforcements arriving.

“All these cop cars everywhere; people were getting hauled away,” he remembers. “We’d kani (ring) the pū from the mountain and we could hear that the pū was coming from all different places … you just hear it coming. Even from way up there, you could holler ‘Kū Kiaʻi Mauna!’ and you could hear the calls coming back from all directions.”

He adds, “It was like another type of battle … not a single fist was thrown.”

Some of the strongest images from that day came from protectors’ steadfast adherence to kapu aloha, while holding down their lines and their positions using chant and prayer to remain strong. Mangauil recalls one wahine protector standing her ground, chanting all the while as one officer threatened to arrest her, then brought in another officer to assist as he handcuffed her. Even as she went down to the ground she continued her chant.

“She chanted the whole time, and during the whole thing she kept her prayers going, Mangauil says. “It was powerful. And it was so emotional.”

Another image emblazoned in Mangauil’s consciousness from that day was that of uncle Billy Freitas, a kupuna and Hawaiʻi County worker who peacefully stood his ground while his fellow employees from the county police department handcuffed and took away his fellow protectors, including his daughter, Kuʻuipo Freitas.

“He was sitting down here with the flag … it was right up here on the gravel. He ended up not getting arrested, but he held for a long time with his chants and his prayers.”

Foundation for the Future

Mangauil says that the foundation for the kapu aloha, for the Mauna Kea movement, for the resurgence of Hawaiian resistance and culture—all of it began long ago and, as fellow leader Kahoʻokahi Kanuha has repeatedly stated, was built within the Hawaiian Public Charter School system.

“The root of this movement is in we kānaka learning our culture. We donʻt have a choice … weʻre already spiritually grounded,” he says.

While Mangauil admits to feeling fear, for him, that feeling was overshadowed by the sense of pride he felt seeing his people stand up for the land.

Knowing he’d soon depart for Poland, I wondered if Mangauil was worried about what would happen in his absence. He was not. He knew that if the TMT crews returned with construction equipment, “everyone’s just gonna drop everything to be here.”

Looking further down the road, to the endgame of this standoff, Mangauil is equally certain that the kiaʻi and the movement to protect Mauna Kea will prevail.

“I’m quite confident that the telescope will not be built. I do have a fear in my heart of what could happen in this standoff up until the point they finally announce that they’re quitting,” says Mangauil. “But that mountain is not to be built on, and the people who are willing to come out and stand to protect it, will.”