Controversy brews over Larsen’s Beach access

KAUAʻI—As plans proceed to fence a trail that runs across private land, the onus is falling on Kauaʻi County to ensure that public access to Larsen’s Beach is maintained.

The issue has been smoldering for months on Kauaʻi, revealing a deep mistrust of private landowners and the county, renewing long-standing concerns about the liability associated with beach access and raising questions about just how easy an access should be.

The controversy arose when Bruce Laymon, whose Paradise Ranch LLC leases Waioli Corp. land fronting Larsen’s Beach, sought state and county permits to clear brush and install new cattle pasture fencing in the conservation district. The work would be funded by a federal Natural Resources Conservation Services grant.

The proposed project would block a trail that runs parallel to the remote beach across Waiʻoli land. It’s the route preferred by some because it’s less steep than another path that descends about 100 feet in elevation to the coastline through an outcropping of rocks.

The Kauaʻi Chapter of the Sierra Club and others have opposed Laymon’s request, citing concerns that the project would block public access and possibly threaten customary gathering rights, nearshore waters, rare species and archaeological sites.

But officials with Waioli Corp. said those using the lateral route have been trespassing for years. They also say the nonprofit kamaʻāina organization is being unjustly accused of trying to keep people from the beach when it has already provided the county with a legal access—the vertical route through the rocks.

“There is already a public access there,” said Waioli attorney Don Wilson. “It’s what the county requested, it’s what the state approved. If people want something different, they should be talking to the county and not bothering Bruce [Laymon] and his legitimate activities down there.”

In 1976, the Kauaʻi County Council approved acquisition of land from Waiʻoli to create public access to Larsen’s. Three years later, Waioli executed a warranty deed to convey a lot with a newly-created dirt road, parking lot, and footpath. Former state forester Ralph Daehler chose the alignment for the trail, which runs down the bluff at the east end of the beach.

The county, however, failed to record the deed, and Wilson said that Waioli finally registered the deed in Land Court, at its own expense, in 2000, thus preserving the public access.

Waioli also initially asked the county to install signs in the area, according to a June 16, 1978 letter to the county engineer’s office from former Waioli Executive Director Barnes Riznik. “We would like one sign on the highway and one at the top of the footpath marking directions with the wording: ‘To Public Beach, Day Use Only, No Camping,’” Riznik wrote. “We would also like a half dozen ‘Private Property’ signs prepared to mark our property.”

The signs apparently were never erected, and over the years, as Larsen’s became more popular, visitors and new residents unfamiliar with the legal route began creating defacto trails through the unfenced Waiʻoli land.

Citing liability issues, Wilson expressed concerns about this practice in a Sept. 11, 2000 letter to the county engineer’s office, where he asked the county to “install a fence, or place boulders, along the pedestrian pathway that begins in the parking area and continues on to the beach, in order to restrict the public’s access to Waioli Corporation’s adjacent property. The entire length of the road from old Kūhiō Highway to the parking area overlooking the beach is fenced, but the portion of the County’s property located beyond the parking area is not fenced, nor is the County-owned pathway clearly marked, and public access from the parking area to the beach is therefore not now restricted to the publicly-owned property.”

The fencing and boulders were never installed. Meanwhile, as beachgoers literally followed the path of least resistance, the alignment of the public vertical trail also shifted westward until it, too, has encroached into Waioli’s land in numerous places, according to both Wilson and county planners.

“If the county would’ve originally fenced off where the trail was, we wouldn’t have this problem today,” Wilson said. He wants to see the trail returned to its original alignment to relieve Waioli of liability.

However, it appears the original route has “become overgrown and inaccessible,” according to written communication from the county planning department that cited several factors, including a wire fence erected 10 to 20 years ago that “may have blocked the trail head of the County’s recorded easement” and “[t]he landowner’s choice to not fence the limits of the County’s public access easement for security and management purposes.”

County officials, including Mayor Bernard Carvalho, Councilmembers Lani Kawahara and Tim Bynum, Planning Director Ian Costa, Parks and Recreation Direction Lenny Rapozo, and others recently visited the trail head to assess the situation.

The county is now moving to survey the vertical access to determine its legal metes and bounds and decide whether adjustments need to be made in its alignment. Wilson said that Waioli would be “open to considering” changes in the trail’s route. In the meantime, county planners said, they will not issue Laymon any permits that would cause the existing vertical access to be blocked and have added conditions to his Special Management Area permit to ensure it remains open.

Some residents, however, remain distrustful of both the county and Waioli, and fear the county will not fulfill its responsibility to ensure that a legal public access is maintained. They say the county has previously not been particularly vigilant in such matters, as evidenced by its failure to record the deed to the Larsen’s access.

They also oppose closure of the lateral trail. On Jan. 2, after circulating a flier that claimed “all Larsen’s Beach access [sic] closing soon,” they staged an “access celebration rally” attended by more than 50 persons. They’re also circulating a petition that calls for keeping the lateral trail open.

Meanwhile, Sierra Club members and others are challenging Laymon’s request for a conservation district use permit, both in an attempt to halt the fence that would block the lateral trail and address what they consider deficiencies in his application. They are also requesting a public hearing on the application, which State Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) Director Laura Thielen earlier denied.

According to letters submitted to Laymon’s attorney and the DLNR, citizens are concerned that the proposed brush clearing and fencing project could destroy native plants, adversely impact wedgetail shearwater and albatross nesting areas, contribute to erosion, and cause cattle manure to flow onto the beach, with resulting harm to the Kaʻakaʻaniu reef and endangered monk seals and turtles.

They maintain that Laymon has not conducted the proper studies to support his claim that the fencing and clearing project would not harm any archaeological and biological resources on the land.

They also contend that the lateral access is part of a traditional ala loa, or coastal trail, that once ran between Waipake and Keālia. However, the historic route of that trail remains unclear, as does the issue of whether the Territory of Hawaiʻi abrogated its claim to that public right of way back in 1943. Wilson also discounted claims that beachgoers have established a claim to the lateral route through years of use, saying “prescriptive rights can’t be claimed against land court property.”

Citizens object as well to Laymon’s proposal to install the fence 110 feet from the beach without first conducting a shoreline certification to determine the exact boundary between public and private land. County planners, however, have said the request for a certified shoreline could backfire, as Laymon could legally install the fence within 40 feet of the line, which would have a greater impact on the beach.

Those who support a lateral access further maintain the vertical access is dangerous and too steep for some beach users to comfortably traverse. But county and Waioli officials said the access was primarily intended to serve fishermen and limu gatherers engaged in traditional, subsistence practices.

“Based on our records, the recorded easement was originally established to correspond to a relatively rugged trail that existed and was used by fisherman and long-time residents familiar with the coastline and the area,” according to information from the county planning department provided by Beth Tokioka, the mayor’s assistant.

“Waioli first considered this because there was a request from fishermen to make access to the reef easier,” said Waioli Executive Director Robert Schleck. “The access was done with the idea of not overwhelming the beach. We wanted a minimal trail to reduce runoff on a pristine reef.”

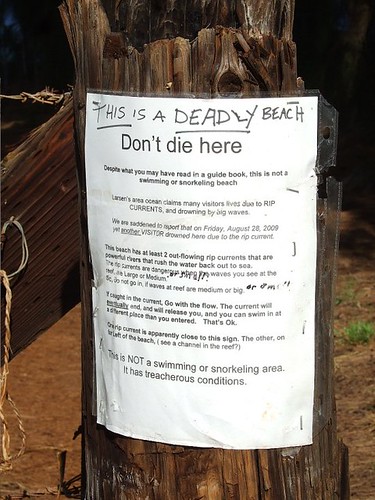

Others have questioned whether it’s wise to make access too easy, especially for visitors. A dangerous rip current forms on the reef when the surf is big, and Larsen’s has been the site of numerous drownings. The beach has no lifeguard or other facilities, such as restrooms.

While the fencing has been proposed as part of a soil conservation project, Waioli officials and Laymon say it also will help resolve ongoing problems with trespassers.

In recent years, newcomers to Kauaʻi began living at Larsen’s in camps on Waioli land. According to correspondence between Schleck and Tarey Low, the state’s Chief Enforcement Officer on Kauaʻi, persons at some 30 different tent sites were warned of trespassing in March 2002. Despite DOCARE action, the camping continued, and correspondence documents that Waioli repeatedly approached the county for “coordinated and sustained” assistance in policing the area, to no avail.

The campers created a health hazard by failing to properly dispose of human waste, and Wilson and Schleck said the Department of Health threatened Waioli with hefty fines if it failed to control the camping.

Laymon and adjacent property owners say the campers also have stolen items from their land, started brush fires, tapped into water lines, left mounds of trash and cut fences, allowing the cattle to wander onto adjacent property and the beach.

The fence lines were cut so often that Laymon refused to put cattle in the area, causing Waioli to lose its agricultural dedication and pay an additional $8,000 in real property taxes, according to an Oct. 9, 2003 letter from Wilson to the late Mayor Bryan Baptiste.

Steve Frailey, who farms noni on land adjacent to the access road, said that Larsen’s is also sometimes used for all-night “rave” parties, and that residents are disturbed by the noise, frightened by some of the campers, and offended by the nude sunbathing there, causing them to avoid the beach.

In a May 9, 2004 letter to Baptiste, area residents expressed their concerns about open fires, illegal camping, marijuana cultivation, lack of sanitation, theft, trespassing, speeding on the access road and nudity.

Frailey said he believes the fencing project will help solve some of the problems that are impacting the “quality of life” for area residents. Following a recent meeting between landowners and the mayor, he said the county is “bending over backward to look at everybody’s concerns.”

But a Sierra Club member who did not wish to be identified said that Laymon just wants to establish himself as “king of the hill” and control access to the beach. And area resident Hope Kallai, in correspondence to Laymon’s attorney, said the community and cultural practitioners been excluded from the project’s planning process.

Currently, the fate of the project lies with the state and county, which have jurisdiction over the permits that Laymon needs to proceed. In a Dec. 22, 2009 email, Peter Waldau, who has been active in the issue, urged Sam Lemmo, administrator of the Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands, to deny the CDUA permit until the issue of the county’s access is resolved.

Lemmo responded: “There is currently unfettered access to Larsen’s Beach and this situation will continue with the new fence if it is approved. You will just have to use the County owned access. Things change in life, and we feel that this is a reasonable change.”

Waioli, meanwhile, remains cool to the prospect of providing lateral access, citing tactics that opponents initially used to block the fencing project and the resulting adverse publicity that coincided with its annual fundraising drive.

“It was a very aggressive approach,” Schleck said. “It’s pretty hard to think that anyone, after being beaten up, would be receptive to negotiations.”