Mechanical chatter: Humans are being replaced just as our parts are being replaced

BakTalk

with Beth-Ann Kozlovich

We are all tellers of tales. We may not write them down, but every day, in uncountable ways, we tell our stories. It’s not easy. And writer Andrei Codrescu believes the sad irony is that the technology we have created to make communication instant has simultaneously created in us such fragmentation that telling our stories is difficult. Yet all the while, we deeply yearn to connect others to us through them.

“There are a number of gigantic changes going on now because of the new technologies,” Codrescu says. “We are talking and telling each other things, but we are not telling each other stories. It’s almost as if we are using words and Twitter and Facebook and all these things to fill a void that stories used to fill. Books are going away, that’s inevitable, so the neat way of collecting stories is gone but our need for them is just as great as ever. Maybe even greater because there is so much chatter.”

Codrescu is a Romanian émigré and has been in the United States since 1966. He has poked at American culture, world history, literature, the absurdity of life for decades. He taught poetry and literature at Johns Hopkins University, University of Baltimore, and Louisiana State University. In 1983, he founded Exquisite Corpse: Journal of Books and Ideas. And in that same year, he became a regular commentator on National Public Radio (NPR) talk show “All Things Considered.” The author of over 30 books of poetry, novels, and essays, plus the writer of a documentary, Road Scholar, which received a Peabody Award, Codrescu has become the insider’s outsider.

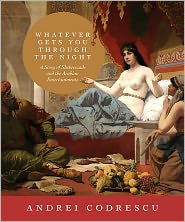

His latest book, Whatever Gets You Through the Night, is a retelling of One Thousand and One Nights. Perhaps given the view Codrescu has of the imminent death of books, his book contains what could be viewed as four separate books that literally wrap around each other. Thankfully, there are enough gaps to allow a little air to get through and imagination to take over. But these stories flow into each other, unlike the bubbles of texts or snippets of Facebook postings that he says distract us.

“The new media allows us to interrupt each other more than tell each other anything,” Codrescu says. “They are forms of interrupting a story. The Library of Congress, for instance, collects all tweets and electronic messaging but I’m not sure what they are going to do with it. There is so much electronic data. There are no humans who can go through it all. One imagines a superhuman robot because there is now no way to take a thread and go through it. I’m not sure how we’re going to make picture of the past from it.”

Codrescu’s vision of our future is far from comforting.

“Humans are being replaced just as our parts are being replaced. I would like to think there is an escape, a back door though stories, through fairytales and through magic, but I think the hard reality is there isn’t,” Codrescu says. “We are Borg and I think that everything that science fiction in its depressing form has given us for the last 50 years is coming true.”

Clearly, Codrescu isn’t happy. Or perhaps it’s that Eastern European proclivity toward melancholia. Or maybe he just could be right. Regardless, and perhaps in spite of how modern life is transforming us, our perspective on better developed technologies, information distribution systems, and content creation are still refining what it means to communicate effectively—and widely.

“It’s very much a question of who the storyteller is as much as what the story being told is because you can take any number of facts and fancies and weave a tale from them and it will serve the interest of the teller or group of tellers,” Codrescu says. “History is told that way, usually by the winners. There are a lot of stories that disappear unless told over and over. Stories perpetuate the myths and power of the tellers. Victims rarely tell stories.”

Yet technology has allowed many victims’ stories to emerge from war zones, oppressive regimes, and daily life challenges. So throwing out the technology to save our humanity is a hollow argument—and not one Codrescu makes. It’s the relational situation in which our technology places us that he asks us to stare down while also heeding our nature to preserve our stories.

“What makes humans perpetuate themselves through stories and what makes stories go on past the lifetimes of individuals?” Codrescu proposes. “That’s a question that’s particularly apt now because we are on the verge of some kind of physical immortality and the robotic talking is almost mechanical chatter.”

Technology continues to advance faster than our sensibilities, Codrescu says, with much of the United States living “on the fumes of the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. In a funny way, we’re more isolated than those people were. Technological innovation has been so rapid and we have so much communication now that we forget that the human-to-human business is actually harder and that we are in fact farther away from each other though we seem to communicate more.”

The duo of globality and globalism have moved us beyond our borders and let us feel connected to everyone on the planet and economically interdependent, but Codrescu says they are also responsible for the collapse of many old and good ways of seeing the world and of collecting those observations ... and why oral tradition and storytelling events are resurging as we continue to see in Hawaii.

“I think the reason why people are starting to look at the very old stories and myths and are trying to connect to origin stories like Scheherazade, the fairytales, and Greek myths—which are again of interest to many people—is that they are trying to find the wellsprings of humanity in ways that have allowed us to have survived this long,” Codrescu says. “There is a great deal of interest in origin, in ontology, in roots because we are on the verge of becoming something else, something posthuman.”

Meanwhile, Codrescu will still continue to write books.

The full interview with Andrei Codrescu is on the Town Square archive at www.hawaiipublicradio.org.