Hawaii’s ‘Living Democracy’ means having a voice, getting private wealth out of politics

BakTalk

with Beth-Ann Kozlovich

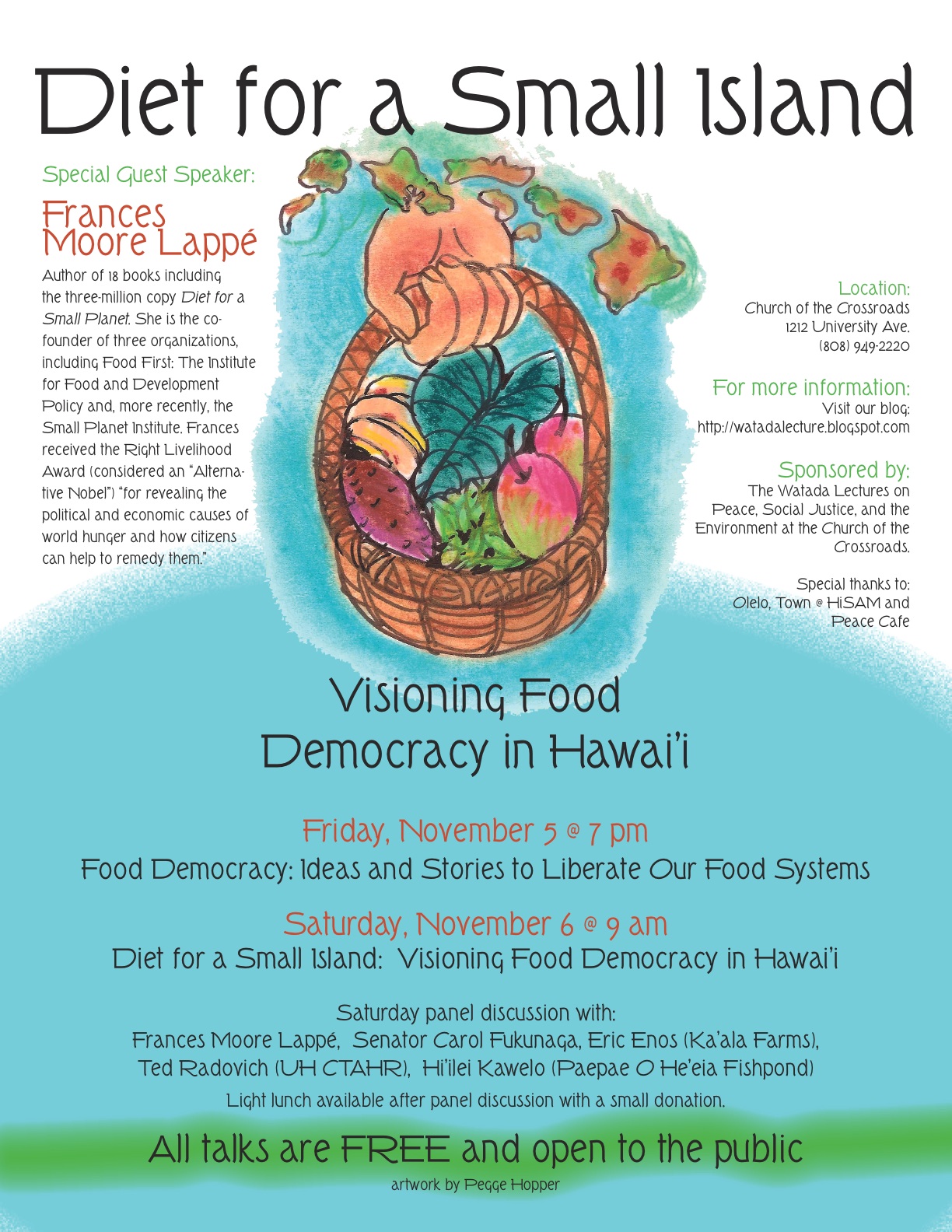

HONOLULU—It would have been tough to be a young adult in the 1970s and not be aware of the phenomenon caused by Diet for a Small Planet. Frances Moore Lappe, then 26, galvanized a generation. The book later became one of “75 books by Women Whose Words Have Changed the World” selected by the Women’s National Book Association. As Diet outlined a shift in attitude toward food production and consumption, her subsequent 17 books—and EcoMind due next fall—incrementally extend her focus to include a call for a more basic and direct experience of democracy. Lappe is in Honolulu this week as the University of Hawaii Distinguished Lecturer to talk about both.

In 2008, Gourmet Magazine named Lappe one of 25 people who changed the way America eats. The list includes Thomas Jefferson, Upton Sinclair, and Julia Child. That same year, she was also named the James Beard Foundation Humanitarian of the Year. Lappe is a 1987 recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, sometimes referred to as the Alternative Nobel; she holds 17 honorary doctorates; and is co-founder of the Institute for Food and Development Policy and the Small Planet Institute. Lappe works with both of her children and says her grandmother status and years on the planet give her a practical body of experience to know what public policy does and does not work.

At the heart of her most recent book is an exhortation to a challenged American public to understand and translate what she terms Thin Democracy into Living Democracy. Getting A Grip 2, the update of the 2007 volume she felt compelled to rewrite following the end of the Bush years, provides a blueprint for activism on the small scale. It details the “spiral of powerlessness” that perpetuates Thin Democracy juxtaposed with Living Democracy and the “spiral of empowerment” that supports it and lays out some simple actions anyone can take.

“We are at a moment where Thin Democracy—meaning a structure of government in and of itself—isn’t enough,” Lappe says. “Living Democracy is a culture, what we do and not what we have. It’s way of life and about making government accountable to us.”

Moving from living in fear and a perceived lack to a world view of creativity and a singular belief in the possibility of plenty may be tough for a lot of people trained to think that the health of the marketplace is tantamount to social wellbeing; and that democracy ends with a free election of leadership. “But the market doesn’t work on its own,” Lappe says. “It only works with a democratic policy where we set the rules.”

Hawaii political analyst, Neal Milner, is a little more circumspect.

“We have to look at issues and decide when it’s the politicians’ problem and responsibility when it’s our problem and responsibility as a community,” Milner says. He also acknowledges that with the amount of nimbyism statewide, citizen activism is often difficult to uncouple from a narrow, individual self-interest.

Yet Lappe’s appeal for a participatory democracy in which citizens are more than spectators and whiners begins with involved problem-solving starting at the neighborhood level. She agrees that takes some critical thinking and organizational skills, which not everyone may have, plus a fervent belief that acting out of personal responsibility is a necessary, worthwhile expenditure of time to create societal change. But she says we’ve been through this before.

“It’s not a mystery,” Lappe explains. “We can look back at the period of the 1940s to 1970s. All of us were doing better and the poorest among us were advancing at a huge rate. We know how to make that work by keeping wealth circulating. What we’ve done since the 1970s is reverse that. Citigroup told us in 2005 that we now live in a plutonomy where 1 percent controls as much wealth as the 90 percent below it.”

Milner says he’s not particularly impressed by the success of grassroots democracy in Hawaii. Often it translates into a kind of selfishness, he says. “I think if we want to do grassroots or neighborhood democracy, formally or informally, we’re going to have to take a different look at what civic life is like,” Milner says. And by extension, we have to consider more carefully how we pass the ethos of community involvement to our children.

“Look, I’m a teacher,” Milner says. “You can’t teach civics. Kids learn by watching, and not always self-conscious watching. This is a hard one in Hawaii. People are busy. About the only way is to do it an issue at a time through churches, synagogues, and mosques. It requires a change in attitude, in culture, and is often antagonistic to the rest of our lives.”

That brings us back to the authentic experience Lappe advocates.

A few days after the end of a very ugly election season topping two of the most economically difficult years in generations, Lappe muses over whether the outcome furthers or fetters our ability to transition from Thin to Living Democracy.

“We’re perhaps in a nadir in one sense of the role of private wealth in our political system and our political system depends on government accountable to the people,” Lappe says. “Yet we’ve allowed the infusion of private wealth because of the SCOTUS decision in January.”

Lappe refuses to refer to it by the common name most of us know: Citizens United. “It’s anything but,” she says. Although she hopes for passage of the Fair Elections Now Act that would allow a candidate to run without private money, she assigns no probability to its passage given the GOP Congressional sweep. “It’s hard to imagine huge positive change over the next year or so, but we need to focus on the roots,” Lappe explains. “Underneath every issue is the mother of them all—getting our voices heard and getting the power of private wealth out of the political system at every level.”

Milner is equally realistic: “In Hawaii, we’re going to have to do better things with perhaps less money, at least in the short run,” and in the long term, develop a broader vision that transcends the limited, negative view of politics Milner believes many hold. “Politics has become a bad thing and we have to get over that.”

Fond of saying, “It’s not possible to know what’s possible,” Lappe says the first step is to move away from blame. All of us, she says, can choose to make activism an adventure to reclaim our political power.

The interview with Frances Moore Lappe and Neal Milner is on the Town Square archive at www.hawaiipublicradio.org. Reach Beth-Ann Kozlovich at [email protected].