Hauʻoli Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea

ʻUmi Perkins takes us through the history of today's national holiday celebrating the return of sovereignty.

July 31 is a Hawaiian national holiday—Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea. In this post I trace some of the historical background of this event, and report on its observance on Saturday, July 26 at Thomas Square, Honolulu. The date is also being observed at National Parks on Hawaiʻi Island.

Lord George Paulet arrived in Hawaiʻi from Great Britain in the year 1843 during the reign of Kamehameha III (Kauikeaouli). Paulet had been sent to investigate British Consul Charlton’s complaints that British citizens were being treated unfairly by the Kingdom. Charlton’s chief complaint, however, was that the former regent Kalanimoku had given him land, but that the new King, Kauikeaouli, was denying Charlton’s purported land ownership “rights.” Paulet demanded that Charlton receive the lands he had claimed, that British citizens were only to be judged by British law, and that a $100,000 indemnity be paid.

Paulet stated that, “If my demands are not met, I will be obliged to take coercive steps to obtain [the] measures for my countrymen.” The Hawaiian Kingdom’s response was to cede the Kingdom to the British military under protest on February 25, 1843. They wrote a protest and appeal to Queen Victoria. They also wrote to Hawaiian representatives who were then on a diplomatic trip to England, and sent a representative to the British Consul in Mexico.

The August 8, 1843 issue of Ka Nonanona, a Hawaiian newspaper read:

AUGATE 8, 1843. Pepa 6.

MOKU MANUWA. I ka la 26 o Iulai, ku mai la ka moku Manuwa Beritania, Dublin kona inoa. O Rear Adimarala Thomas ke Alii. He alii oia maluna o na moku Manuwa Beritania a pau ma ka moana Pakifika nei. I ka loaa ana ia ia ka palapala no Capt. Haku George Paulet, ma ka moku Vitoria, a lohe pono oia, ua kau ka hae o Beritania ma keia pae aina, holo koke mai no ia e hoihoi mai ke aupuni ia Kamehameha III. Nani kona aloha mai i ke alii, ea! a me na kanaka no hoi.

KA HOIHOI ANA O KE AUPUNI. Nani ka pomaikai o Kamehameha III, a me kona poe kanaka i keia wa, no ka mea, ua hemo ka popilikia, ua hoihoiia mai ka ea o ka aina. Ua pau ka noho pio ana malalo o ko Vitoria poe kanaka. O Kamehameha III. oia ke alii nui o Hawaii nei i keia manawa. Ua kuuia ko Beritania hae ilalo i keia la, Iulai 31. 1843, a ua kau hou ia ko Hawaii nei hae. Nolaila, eia ka la o ka makahiki e hoomanao ia’e, me ka hauoli, ma keia hope aku.

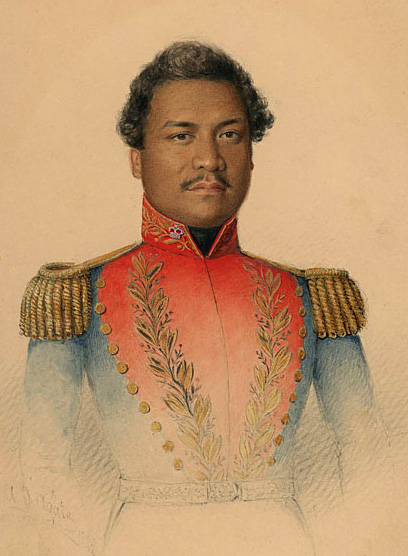

Kauikeaouli Kamehameha III

Rear Admiral Richard Thomas

.jpg)

Lord George Paulet

My rough translation:

BATTLESHIP. On the 26th day of July, a British battleship anchored here; Dublin was its name. The captain (Alii) was Rear Admiral Thomas. He is the head [alii] of the British Pacific fleet. In the taking of the documents of Capt. Lord George Paulet of the ship Victoria, he listened fairly [to how Paulet] raised the flag of Britain in this archipelago, [and] decided quickly to return the government to Kamehameha III. Amazing is the love of the alii for [the] sovereignty [ea]! And the people also.

THE RETURN OF THE GOVERNMENT. Splendid was the gratitude of Kamehameha III and his people at this time because the trouble [crisis, popilikia] was removed, and the sovereignty of the land was returned. Finished is the captive occupation under Victoria’s people. Kamehameha III is the King [Ruling Chief, alii nui] at this time. The British flag is lowered [put down, kuuia] on this day, July 31st, and Hawaiʻi’s flag flies anew. Therefore, it is a day of the year to remember joyfully from this day forward.

It was at this time that Kauikeaouli made the statement that became the Kingdom’s and later the State’s motto: “Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono,” or “The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.”

Seen in this context, it is obvious that Kauikeaouli’s statement is about the return, or perpetuation, of sovereignty, and not merely a poetic statement about the “life of the land.” As I mentioned in my TED Talk, the motto of the State of Hawaiʻi is a sovereignty slogan for the Hawaiian Kingdom, which denies the existence of the State of Hawaiʻi.

Peter Young describes the feast that took place at Kaniakapupu in Nuʻuanu to celebrate the restoration of sovereignty:

271 hogs, 482 large calabashes of poi, 602 chickens, 3 whole oxen, 2 barrels salt pork, 2 barrels biscuit, 3,125 salt fish, 1,820 fresh fish, 12 barrels luau and cabbages, 4 barrels onions, 80 bunches bananas, 55 pineapples, 10 barrels potatoes, 55 ducks, 82 turkeys, 2,245 coconuts, 4,000 heads of taro, 180 squid, oranges, limes, grapes and various fruits. (source: Peter T. Young, Hoʻokuleana, LLC, 2014)

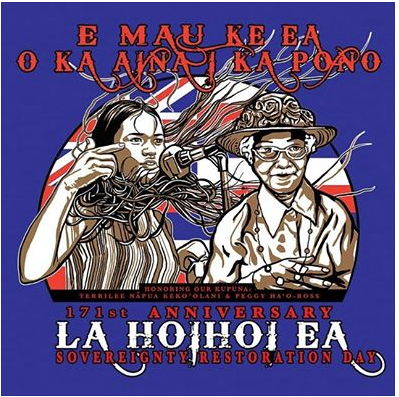

Poster for 2014 Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, honoring Terri Kekoʻolani Raymond and Peggy Haʻo Ross

2013 poster for Lā Hoʻihoʻi, honoring Kekuni Blaisdell and Soli Niheu

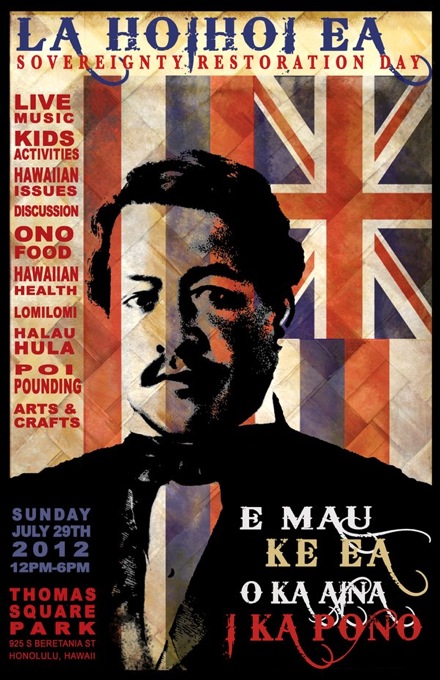

2012 poster for Lā Hoʻihoʻi

It wasn’t until 1987 that Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea began to be observed again. In 1988, at age 16, I attended a very early sovereignty rally with my mother, a professor of Hawaiian literature. The rally was organized by Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell, who is now considered the father of the sovereignty movement. Neither I nor my mother had considered the prospect of Hawaiian sovereignty, as Hawaiʻi was still at the tail end of a process of Americanization, with “local” people trying constantly to prove they were “American enough.”

Yet here was a Hawaiian, very successful in the newly-Westernized Hawaiʻi, advocating the idea of not being American at all. It was a difficult idea to grasp, but within five years the notion that some model of sovereignty would be implemented was considered inevitable.

Last year, the movement began to become nostalgic of itself, recognizing that its early leaders seemed to be reaching the end of their lives. Two men, Blaisdell and activist-extraordinaire Soli Niheu, were the honorees at the Thomas Square celebration.

This year, two women, Terri Kekoʻolani Raymond and Peggy Haʻo Ross were honored there. Kekoʻolani spoke of others who were instrumental in the early movement, and Haʻo Ross was represented by her daughter Liliʻuokalani Ross, who gave an overview of her life and activism.

Music and commentary by Skippy Ioane, Imaikalani Kalāhele (who is a kind of Hawaiian beat poet), Liko Martin (with Laulani Teale) and others was consistent in its themes of Hawaiian steadfastness and solidarity to the concept of pono.

It may have been a sermon delivered to the choir, but KITV news covered the event, spreading its message to others who may not already hold these views.

And still we say, “Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono.”